Two Amendments on the Senate

Some Constitutional Amendments: Let's try this again, from the top.

Many writers propose constitutional amendments in order to demonstrate their fantasy vision of the perfect regime. In Some Constitutional Amendments, I propose realistic amendments to the Constitution aimed at improving the structure of the U.S. national government, without addressing substantive issues.

If our system was still enlightened enough to take this problem seriously, we could probably solve it. It applies to Senates as well as Presidents.

The Story So Far…

In Part I: “A Senate, If You Can Keep It,” I identified the Senate’s purpose as a “control rod” regulating the untempered power of democracy in the House, gifted with distinct virtues thanks the very different character of its electorate (state legislators). I then traced the Senate’s collapse into the pathetic shell of a deliberative body it is today.1

Today, I’m going to try and fix that collapse.2 To that end, I offer not one amendment… but two!

Amendment XXXIII

Section 1. The Senate of the United States shall be composed of one Senator from each State.

Section 2. In the first twelve months after this article becomes part of this Constitution, each state shall, under such rules as Congress shall prescribe, be simultaneously deprived of one of its senate seats, as randomly as possible, while preserving the equality of the three classes of the Senate. To fill the state’s remaining seat for the remainder of the current term, the state shall hold a senate election as prescribed by this Constitution, except that the only eligible nominees shall be the U.S. Senators from that state as of this article’s ratification.

Over the centuries of glorious expansion in our Republic, the deliberative, tight-knit Senate that the Founders envisioned has grown from 26 seats to 100. That’s just too large a body for tight-knit deliberation.

It is vastly larger than any state senate. (The largest state senate, Minnesota’s, has 67 members. The smallest, Alaska’s, has 20. The average state senate has 39 seats.3 The 100 members of our modern federal Senate, by contrast, almost outnumber the 105 members of the Founding-era House, which they understood to be a huge, rowdy body! To aid the Senate in its mission, we should shrink it.4

This has to be done very carefully, because the Constitution guarantees every state equal suffrage in the Senate. This cannot be altered, even by a constitutional amendment, not even for one day, without unanimous consent from the states. Amendments are hard enough to pass without seeking unanimous consent, so we will maintain equal suffrage while reducing that suffrage from two per state to one per state. As with other complex amendments, some of the implementation details are left to Congress.5

Amendment XXXIV

Section 1. The members of the United States Senate shall be chosen, in each state, by the least numerous branch of the state legislature thereof, being composed of at least ten members, and whose concurrence is necessary for any act of the state legislature to become law.

Section 2. Within thirty calendar days of an imminent or actual vacancy in the state’s Senate seat, the electoral house shall convene to elect a replacement. Upon a motion and a second nominating an eligible candidate, the body shall immediately vote by secret ballot whether to elect that candidate or not. If two-thirds of members present concur, the nominee is elected. If not, the nominee may not be re-nominated for this vacancy under this section, and the mover and seconder may not move or second another motion for this vacancy under this section. If there are no further nominations, or if no U.S. Senator is elected in this way within two calendar days, the body shall proceed to a contingent election under Section Three.

Section 3. In a contingent Senate election, the electoral house shall nominate U.S. Senate candidates by secret ballot, each member’s ballot bearing the name of one eligible person, or the words, “I decline to nominate.” These ballots shall be tabulated in the presence of the entire house. Each eligible person nominated by at least one-tenth of those present shall be a candidate.

Then, the body shall immediately vote by secret, ranked ballot. Any ballot that does not rank all candidates shall be invalid. Each ballot may separately veto up to one candidate. A ballot with more than one veto shall be valid, but all its vetoes shall be deemed void.

Any candidate receiving a total number of vetoes greater than or equal to the number of valid ballots cast divided by seven-tenths the number of candidates shall be deemed eliminated.

Of remaining candidates, if one candidate defeats all others head-to-head, that candidate shall be elected.

Otherwise, the smallest set of candidates shall be identified, such that each candidate in the set defeats every candidate outside the set head-to-head. The candidate with the fewest highest-ranked votes who is not in that set shall be eliminated. If there is now a single candidate who defeats all others head-to-head, that candidate shall be elected. Otherwise, candidates shall be eliminated in this way until a candidate is elected, eliminating candidates in the set only if all other candidates have already been eliminated. Exact ties shall be broken by lot.

Section 4. Any pledge, vow, oath, or any other commitment by a Senate elector regarding his votes to nominate or elect a U.S. Senator shall be null, void, and utterly without force from the moment it is made (excepting her oath to this Constitution and her state’s Constitution), and no Senate elector may be compelled to make any such commitment. Any instruction, advice, or requirement laid upon an elector regarding same, outside the provisions of this Constitution, shall be likewise null and void.

Section 5. The seventeenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed. This amendment shall not be so construed as to affect the election or term of any Senator chosen before it becomes valid as part of the Constitution.6

The Senate was supposed to be composed of wise and skilled lawmakers, each with “due acquaintance with the objects and principles of legislation.”7 They were to be elected from state legislatures, to reflect the interests of those states (not the People directly) in the corridors of federal power. This different constituency would give them different virtues (and different vices) than the House of Representatives, one more layer in the Founders’ subtle system of check and balance. Senators were expected to be results of a state consensus, because the Founders did not anticipate political parties. Indeed, they mortally feared political parties, and pinned many of their hopes on the notion that the nation would instead be governed by many loose and fluid coalitions led by wise men who would never place the interests of their temporary “faction” above the permanent interests of their nation, their state, or their branch.

The Founders plans were spoilt, because organized political parties formed anyway (as they must).

First, the parties put a stop to that whole “state consensus” business. Senators were soon elected, in effect, by their party caucuses, with the usual results:

Gradually, as partisanship took root at every level of the nation, the wider political party organizations supplanted the party legislative caucuses.

The People, realizing that the state’s positions in the Senate would swing wildly from election to election based on which party controlled the majority in the state legislature, began to vote for state legislative candidates, not for their positions on the issues nor their merits as legislators nor for their good character, but for the letter next to their name. Their analysis was not wrong, but their tactics changed the character of state legislative elections into proxy votes for the federal Senate. Senate deadlocks began to occur more frequently,8 as increasingly national parties became less willing to compromise.

The parties realized they could win more elections with honey than vinegar, so they stopped paying so much attention to qualifications like “acquaintance with the objects and principles of legislation,” and started looking for charismatic public speakers who’d play well for the party on the stump… or, in other words, demagogues.

State legislators, frustrated that they often no longer mattered in their own elections, tried desperately to separate themselves. They persuaded their parties to institute “primary elections,” where the party’s supporters chose the party’s Senate candidate directly. A rapidly growing collection of states even passed laws holding statewide “advisory elections” and pledging their legislatures to elect the winner to the U.S. Senate. Maybe then the People would start caring about state issues in state elections!9

The Seventeenth Amendment made popular election for U.S. Senate the law throughout the country. This destroyed the Senate as an institution, and we live in the still-smoldering wreckage (which occasionally implodes down into hitherto-unknown subbasements), but the Seventeenth was only the final surrender to a system that was, by 1912, already in free-falling collapse.

This amendment proposal restores the Founders’ design, while accounting for the existence of organized political parties (and populist pressure from outside). Let’s examine its provisions one by one.

Section 1: Back to the States

First and foremost, this proposal returns U.S. Senate elections from the ballot box to the state legislature.

However, a number of problems arose from the Constitution’s original charge that senators must be elected by a double majority: both houses of the state legislature, simultaneously. It was hard to get two houses to agree on a candidate if the two houses were controlled by opposite parties. As a matter of fact, it is hard to get two legislative houses to agree on anything, which led many states to elect U.S. Senators in joint sessions of both houses, blurring the Constitution’s original intent. However, joint conventions of state house and senate are still harder to manage than single-house proceedings. There’s a lot more egos to stroke and much more complicated lines of negotiation.

Even the floor rules are messier! Rules for joint sessions aren’t as clearly defined, nobody knows them as well as the rules of their home house, and there’s far fewer precedents fleshing them out. There are lots of people out there eager to exploit ambiguities in the floor rules,10 so “less robust rules” is a serious drawback.

Thus, this proposal simplifies: it assigns election of U.S. Senators, not to both houses of the state legislature, but to the state senate alone. (It seemed appropriate.)

Of course, the proposal can’t just say, “state senate,” because not every state has a senate. Nebraska has a unicameral legislature. All states with a bicameral legislature currently call their upper house “the senate,” but they don’t have to. New Jersey calls its lower house the “General Assembly,” not the more common “House of Representatives,” so, in the future, a state could rename their state senate something else, like “Sheev Palpatine”:

So the amendment includes some general language about the “least numerous branch of the state legislature” that captures all state senates and the Unicameral.11

However, we can’t just return senator election to the legislatures, or even to the state senates, and call it a day. After all, that’s the system that was in place until 1912… and that system was already broken! We still must address the problems of proxy election and popular, partisan control over the nominees.

Section 2: Require a Consensus Senator

[Text]12

The next section of the proposal gives the state senate two days to freely elect someone (with just a little extra language to prevent state senates from stalling). However, to win at this stage, the candidate must win a two-thirds supermajority.

This supermajority requirement has two benefits.

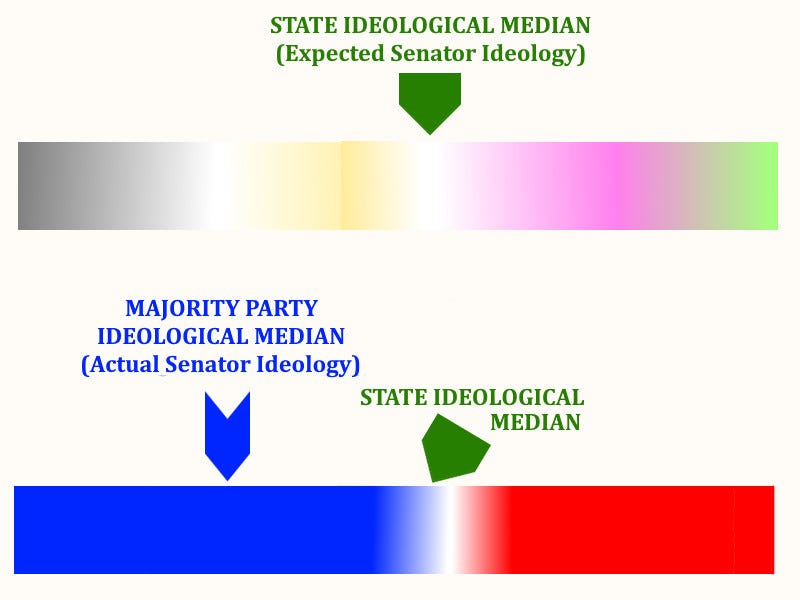

First, in any state that is even slightly purple,13 it will be impossible to achieve a two-thirds supermajority without at least some votes from the minority party. This gives the minority party leverage to force a candidate who is broadly acceptable to all parties. That pushes the elected senator away from the majority party’s ideological center and toward the state’s ideological center.14 So this requirement directly addresses one of the shortcomings of the current Senate.

Second, the supermajority requirement helps break down party discipline, enabling the greater independent judgment we’re seeking for our state legislators. It gives leverage to the minority, and even to factions of the majority—leverage which can be used to pry majority members apart from their party bosses. “Of course I wanted to vote for our party’s wonderful nominee,” they can say, lying, “but that darned minority party wouldn’t accept him, so we had to find a compromise.” If that compromise happens to be someone everyone in the state senate recognized as a better candidate all along, so much the better.

The secret ballot further erodes party discipline by allowing legislators to vote their conscience without being caught and punished for it. We want state senators, in this case, to exercise independent judgment based on personal experience and relationships, rather than towing the line or fearing backlash from constituents who have been enraged by something they saw about the race on social media. The secret ballot gives them that freedom of judgment.

Once party discipline breaks down, so does the mechanism that changed state legislative elections into proxy elections for the federal Senate. Once there’s no longer a clear relationship between a state senator’s party and the final outcome of the federal Senate race, voters have fewer incentives to vote a party line just to win a senate seat.

Finally, this requirement is more likely to lead to stability in state policy (and, ultimately, federal policy) over time. If, in a given state, Republicans enjoy a thin majority over the Democrats, the only road to a two-thirds majority probably goes through a moderate Republican. When the Democrats take back that narrow majority, their only road to a two-thirds majority likely goes through a moderate Democrat… or perhaps even the same moderate Republican, who will, by this point, have certain seniority privileges, certain allies, and certain experience navigating the federal Senate, that could benefit the entire state. (Of course, the moderate Republican or Democrat would have to be pretty darned moderate to carry off this balancing act over multiple terms.)

Now, I’m a partisan at heart. I hate moderates. However, my flavor of partisan maximalism belongs in the House of Representatives. A large part of the Senate’s purpose is to counteract sentiments like mine. Let no one touch my bloody-minded, red-meat partisan attack dogs in the House, but our design for the Senate must set this aside, or partisan excesses will poison the whole system. Indeed, they already (very obviously) have!

Section 3: Contingent Election

Alas, sometimes, an electoral body cannot reach a consensus for a long time. Indeed, under the Founders’ system, it could take divided state governments months, or even years, to elect a senator, and that was with only a simple majority required (albeit in both houses). Because this amendment imposes a two-thirds requirement, it is much more likely to cause deadlock.

Rather than allow the minority to stall out the majority indefinitely,15 the proposal forces everyone to a contingent election after two days. This process is unpleasant for everyone. Rather than an agreed-upon candidate, there’s a lot of finicky details to ensure that, essentially, nobody who reaches this stage gets their first choice, or perhaps even their second choice. This, in itself, is a strong incentive for the two sides to get together and make a deal before it comes to this point. I expect that it will rarely come to this point, so much of what you are about to read would be irrelevant in most elections. Nevertheless, sometimes, it will come to this point, and we had better be prepared.

The Nominations Phase

[Text]16

In this contingent election, nominations are open to any qualified resident of the state, but each state senator can nominate only one candidate,17 and each candidate needs the support of one-tenth of the body to reach the next stage. In effect, this places a hard cap on the total number of nominations: no matter how large the body, you will never have more than 10 nominees.18

Naturally, the political parties, as well as caucuses within each political party, will coordinate their nominations to ensure certain candidates are nominated. If either party held some sort of public primary election, they will almost certainly make sure to nominate whoever won that election—and these primary winners will, as usual, reflect ideological extremes, not the state’s median. Factions within each party may also choose to nominate. However, both parties have strong incentives to nominate as many candidates as they possibly can. This is because of the veto, which we’ll get to in a moment.

Once the nominees are announced,19 the body votes by secret, ranked ballot.20 However, any voting system that allows open nominations followed by ranked-choice vote can be effectively manipulated by a bare majority to force their preferred outcome. In other words, if we immediately counted votes at this point, the majority could manipulate either the ballots or (more cleverly) the list of nominees to effectively guarantee victory to the winner of their party primary.21

The Vetoes Phase

[Text]22

That is why this system incorporates vetoes. Nominations are open, but the minority party (and other small coalitions) can act together to narrow the list back down, eliminating primary winners, unacceptable candidates, or candidates nominated solely to manipulate the ballot-counting. Of course, the majority party can do this, too!23 As each side eliminates unacceptable candidates, they leave behind acceptable ones, forming the basis to force the compromise they failed to make in Section Two. Overall, we’ll usually expect around two-thirds of the nominees to be eliminated at this stage. Here’s how that works:

Alongside their ranked choices, each state senator’s ballot includes up to one veto. These are tallied immediately. If any candidate receives a certain number of vetoes, that candidate is eliminated from all remaining rounds of counting.

The veto threshold varies based on the size of the house and the number of nominees: “the number of valid ballots cast divided by seven-tenths the number of candidates”. For example, in a 39-person state senate with 9 nominees, the veto threshold is 7.24 If that same senate puts up only 3 nominees, however, the veto threshold nearly triples, to 19.

This veto threshold ensures that any sizable25 minority party will have the power to veto at least one majority-party nominee, but that the majority party will not be able to veto all the minority-party nominees. This leaves the majority in the driver’s seat, but gives the minority real leverage. The minority can offer a serious compromise candidate as a carrot… and veto any clear majority favorite as the stick.26

The minority party will, in general, nominate as many candidates as it can, because more nominations lead to a lower veto threshold, which, in turn, gives the minority more leverage against the majority. The majority party has a good incentive to do the same thing, since, if it nominates only one or two people (in order to keep the veto threshold high), the minority stands a real chance of eliminating all the majority-party candidates. (Again, the veto mechanism allows well-coordinated voters to eliminate around two-thirds of the nominees.27) Any party foolish enough to hold a primary of some sort and choose an official “standard-bearer” will be disappointed when that standard-bearer inevitably gets vetoed.

If parties are nominating broadly and voting more or less sincerely, we will at this point find that extreme candidates in all parties have been knocked out by the veto, leaving only plausible compromise candidates in the field. If parties are nominating strategically and vetoing tactically (they will), we expect… more or less the same thing. Neither party can put forward an official “standard-bearer” without the other party’s consent. A too-greedy majority party could arrange things to ensure that its last candidate standing is an extremist, but that merely opens the majority to a tough vote between that extremist and the sensible moderate nominated by the minority.28

The Condorcet Phase

[Text]29

Once the vetoes are settled and (roughly) two-thirds of the candidates are eliminated, we proceed at last to counting the votes.30 This final phase is, in many ways, the least important. The most crucial choices are made in the nomination and veto phases.

To count the votes, we simply check whether there’s a Condorcet winner: if there is one candidate who would beat every other candidate in a head-to-head matchup, she wins. This method tends to elect more moderate candidates acceptable to all, especially if voters are sincere. For example, if Robbie Right-Wing, Millie Moderate, and Larry Lefty run in a chamber with 45% right-wingers, 20% moderates, and 35% left-wingers, Millie should win: she beats Larry 65%-35% and she beats Robbie 55%-45%. A Condorcet count ensures that she does.

Of course, party discipline and tactical voting can subvert this moderation tendency pretty badly, so we aren’t counting on it. On the other hand, we have given legislators the secret ballot and we’ve prohibited bullet ballots. This allows partisans to evade party discipline more or less undetectably. That strengthens the consensus-seeking heart of Condorcet voting.

In the very unlikely event that there is more than one Condorcet winner (ties happen!), we break it using Benham’s method. Benham’s method eliminates the least-popular candidates,31 one by one, and recounts after each elimination until there is a winner. In a previous article, I wrote much more about Condorcet winners and Benham’s method, so if you want more, check there.

Summing Up the Contingent Election

Overall, this method of election works very well when all voters are acting sincerely (with parties exercising little or no control), but it still works pretty well when both parties have strong control.32 Where the system tends to fall short is when one party (whether the minority or the majority) has more control over its caucus than the other. (I’ve put some example elections in this footnote for your perusal, all of which assume highly coordinated parties.33) The system therefore encourages participants to build cross-party trust and mutually disarm.

Indeed, if parties are powerful, Section Three elections force them both to work very hard, under heavy restrictions, only to leave them, in the end, with probably the same U.S Senator they would have had if they’d just made a deal during Section Two. This gives all sides an incentive to just make that deal during Section Two and save themselves the trouble! That’s why I anticipate that, while this contingent election system is robust (and needs to be), it will rarely actually be invoked, because parties will re-learn how to make deals. In the long run, that, too, is likely to bring forth a better breed of U.S. Senator.

Section 4: No Binding

[Text]34

This section of the proposal does relatively little real work. The power of the parties over U.S. Senate election is mostly broken by the secret ballot, the prohibition of bullet ballots, and the two-thirds requirement in Section Two.

However, parties will certainly keep trying to exercise formal control over their state senators anyway, principally by extracting pledges and oaths from them. The few honest men still in politics may consider pledges and oaths morally binding, even though they are not legally binding. This could give parties undue leverage over those honest politicians… or force those last few honest men out of politics! Neither is desirable, so Section Four simply removes the power of political parties (or states) to extract commitments that are binding legally or morally.

While other provisions erode the parties’ informal powers over the U.S. Senate election, this provision demolishes their less important formal powers.

Section 5: Boilerplate

[Text]35

When you repeal an amendment, it is important to do so explicitly. We do not, after all, want there to be any argument that Governors or voters retain the power to fill midterm vacancies by appointment. It is equally important to clarify the limits of the new amendment; here, I borrow language from the Seventeenth Amendment that clarifies that nobody elected by the people will be thrown out of office or subjected to legislative election before the end of their regular term.36

Alternatives Worth Considering

At any actual Article V convention of the states, many proposals will be debated. I think my shrink-the-Senate proposal is simple and speaks for itself. However, when it comes to replacing the Seventeenth Amendment, there are a lot of ideas on the market. Obviously, I think mine’s the best. However, other delegates might disagree, and it may become clear that my proposal is non-viable. At that point, my supporters must consider alternatives. Some of them are worth considering!

Others are not. The main thing you need to watch out for is: will this proposal actually return power over the election of senators to the state legislature? Or does the proposal simply claim to return that power to legislatures, while actually turning state legislative elections into proxy races for U.S. Senate, or giving the governor effective control over nominations? Or, alternatively, does the proposal ratify the destruction of the Senate’s deliberative character (perhaps by massively expanding it), or otherwise encourage Senators to behave badly?

Here are some possibilities that, in my opinion, stand a real chance at succeeding, and are worth supporting if my proposal is non-viable:

Make Mine a Conclave

Conclaves are great. You can shatter all kinds of electoral coalitions if you lock everybody involved in a building by themselves, turn off their phones, take away the cameras, and refuse to let them come out until they reach an honest two-thirds consensus. I’ve told you the conclave (not the Holy Spirit) is the great strength of the Catholic Church’s papal electoral system and I’ve told you (even earlier) that we should elect the president by a conclave of the governors, so why not elect the Senate the same way, given my priorities of a consensus candidate, a wise statesman, chosen without undue influence from political parties?

I avoided this because I think the difficulty of securing so many senate elections is high, and any security failures create a risk of deadlock, and deadlocks were one of the main things that killed the original Senate election system in the first place, so this seemed politically and logistically infeasible. However, in principle, I don’t have a problem with it, and would support it if that’s where the convention was heading. I particularly liked this suggestion from Andres Riofrio:

Hmm… if [the contingent election] is meant to be a painful threat and backstop to avoid deadlocks, couldn’t we keep the regular election at first, and use the threat of a secluded conclave (where they’re not allowed to leave until they choose) as the backstop?

This way (it seems) most of the costs of the conclave process are avoided because state senators would much rather come to a compromise while they’re still free and home, especially since they’ll be forced to make the exact same kind of compromise eventually, but behind gates and potentially far from home.

This is a good idea. I like it. By using the conclave only as a backstop (just like the contingent election in my proposal), it greatly reduces my worries about it.

Stick ‘Em In A Hat

In a previous piece, I said, “I have a deep and abiding fondness for election by sortition. Injecting an element of randomness into elections probably does not reduce candidate quality, but probably does reduce candidate ambition.” This led Mathematicae to suggest that we just replace Section Three with random selection. If, after two days, the state senate can’t come to a two-thirds agreement, then, instead of holding a complicated contingent election like I proposed, we could just put every person who was nominated and received some reasonable number of votes (say, 30%) into a hat and choose the winner by lot.

I don’t love this, because it is very “swingy.” It sets a minority party up, in particular, to reject all compromise in order to roll the dice on maybe getting one of its favored candidates through. How does the majority respond? Naturally, by putting up someone extreme and unpalatable of their own, as a sort of threat, in order to force the minority to bargain honestly. (Because, in this system, each legislator can only support one nominee, the majority will always have more nominees and more names in the hat.) I am okay with this system because I think this threat will probably, usually, work!

But if it doesn’t, you’re liable to end up with U.S. senators even less representative of their states’ ideology than we have today. Across the country, on average, this will cancel out, as a lucky left-wing extremist who drew the short straw will be countered by a lucky right-wing extremist who drew the short straw. Yet you could see a right-leaning purple state like Ohio suddenly represented by a Bernie Sanders type, or Minnesota suddenly represented by a Ted Cruz type. That’s a risk I’d prefer to avoid, especially because I think the People would rebel if it happened often. Nevertheless, I think this system would, on the whole, almost certainly still be a great improvement on the current system and on the original Seventeenth Amendment, so I would support it if I couldn’t get my proposal across the finish line.

Blunt-Force Trauma to the Nominees List

In my proposal, if the consensus election fails, the fallback contingent election selects the winner by ranked-choice voting. However, I have written that, for elections with few voters, “any voting system that allows open nominations followed by ranked-choice vote can be effectively manipulated by a bare majority to force their preferred outcome.” In my proposal, I addressed this problem by following open nominations with a veto round, allowing the minority (and majority) to tactically narrow the list.

There are, however, other ways to narrow the list. You could use an algorithm, like DW-NOMINATE, to automatically throw out candidates who do not hew pretty close to the state’s median voter. I proposed exactly that in a previous attempt at this proposal. There are lots of problems with this approach, but, if the delegates liked DW-NOMINATE, or found some better answer to the problem, it’d be worth considering.

Tuning the Veto

There are several methods that are virtually equivalent to mine, but with a different veto threshold. Various techniques to find the “least hated” member of the body (like this one, proposed by Gilbert) boil down to this method, except for allowing (indeed, requiring) way more vetoes. This is fine and worth considering as an alternative, even though I don’t love some of the expected consequences.

On the other hand, I’m wary of methods that try to allow fewer vetoes than this method. If the minority doesn’t have adequate veto power, the majority will begin to find ways to reliably wrestle its preferred candidate into office, and the Senate will break down in many of the same ways as it did the last time we tried this.

Tuning the Details

Maybe the delegates like the whole proposal, except for the part about using Benham’s Method as a tiebreak. Maybe they’d rather use Hare elimination, or just jump straight to drawing lots like we usually do when there’s a tie. Fine by me! (It would certainly allow us to delete a lot of words in Section Three!) Maybe delegates would rather see the U.S. Senate elected by state houses, instead of by state senates—or even go all the way back to election by joint session, for some reason. Okay!

I wrote the best amendment I could, but you can’t get married to implementation details in a constitutional convention, as long as your broad objectives are being met. There are lots of details that could be changed here without compromising the objectives. (There are also lots of details that cannot. The trick is knowing the difference!)

A Senate for a Polarized Century

Today, we have a broken Senate. It was designed to protect states from the encroachment of the federal government, and to provide a counterpoint / containment system for the populist demagoguery that was sure to dominate the House. It has instead become amplifiers for both. Many people have come to believe the Senate is redundant and ought to be abolished. If the choice is between the Senate as it exists today and no Senate at all… I hate to admit that those people are right.

However, that isn’t the choice we face. Leaving aside the fact that small states can (and will) prevent the Senate’s abolition unto eternity, we could also try to fix the Senate.

These amendments are an attempt to do so. The first proposal shrinks the Senate so that it can be a more focused, deliberative, even intimate body. The second proposal changes the Senate electorate back to a small group of well-informed legislators (rather than a mass mob swayed by feelings and campaign ads), insulates those legislators against partisan pressures, presses them toward consensus candidates who reflect the state’s median voter, and provides insurance against deadlocks.

You wanted to get money out of politics? “Campaign finance reform” and overturning Citizens United doesn’t work (and would be a bad idea even if it did). The way you get money out of politics is by making money less necessary for politics, and the way you do that is smaller, more tight-knit electorates. In the Senate, that means transferring power to a smaller elected body. In the House, it means much smaller districts. There was a lot less money in Senate politics before the Seventeenth Amendment, and we can do it again.

These amendments’ ultimate aim is to not simply to change the Senate’s structure, but to renew the Senate’s culture. Unfortunately, since culture is the result of human choices, I cannot prove this will succeed the way you prove a theorem. All we can do is create structures that create the right incentives, and hope that those incentives lead to more humans making more good choices a lot more of the time.

As the saying goes, though, “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.” I think this proposal creates the right incentives, in a manageable package that voters can understand. There are other options, too.

We cannot abolish the Senate. We cannot neuter the Senate. The small states will never allow it. However, we can fix the Senate. We should choose to try.

Next Voyages: When Some Constitutional Amendments (eventually) returns, I expect to take a pause to discuss why I am doing this, since constitutional amendments seem so impossible right now. After that, my inclination is to move on next to Article V, aka the reason constitutional amendments seem so impossible right now. However, it will likely be a minute. I feel a Catholic spasm coming on.

There were two other parts in the series: “Replacing the Seventeenth Amendment,” which proposed a solution which you, the De Civ readership, roundly rejected as complicated, unwieldy, impractical, gameable, and, in general, bad.

This was followed by an even longer article, “Fixing the Senate, Part III,” where I discussed all the comments. (This, naturally, spawned even more comments, many of them quite useful!)

Parts II and III make fun reading, and go a long way toward showing how I got to today’s proposal. However, they are not essential reading today.

P.S. Those of you who responded to Parts II and III obviously shaped today’s piece in many important ways. Several of them will be obvious. I read every comment, and I hope I “liked” all of them. This article is pretty obviously a major revision of Part II, which came about thanks to your good offices. Now, whether you agree with this revised approach is a question only you can answer! Nonetheless, I appreciated all your feedback.

…again. These proposed amendments are clearly a second draft of my first proposal. The outline of the article will be familiar to everyone who read the previous installments. This is necessary, so all the other readers can still follow along. However, since I don’t want to bore you to death, I changed most of the actual words. Also, a little ways down (in Footnote 6) I’ll summarize the changes between drafts, just in case you want to skim a little. (Obviously, the really big changes are in Section III of the second proposal.)

The median state senate, if you’re curious, has 38 seats. Kentucky, Michigan, and Rhode Island all share this distinction.

A bonus for those who are concerned about population distortions in the electoral college: halving the size of the Senate takes care of a lot of that distortion. Of course, I would replace the electoral college with a gubernatorial conclave anyway, but still worth mentioning.

Here is one possible implementation:

Congress picks a Date Certain within twelve months of ratification. It doesn’t need to be far in the future, but it ought to be far enough away for states to hold an intervening special Senate election.

Currently, Senate Class 3 is the largest, with 34 members to 33 for the others. Congress puts all the Class 3 seats in a hat/bingo roller/lottery ball blower and randomly selects one. (Let’s say Idaho’s Class 3 seat gets picked. The seat is currently held by Mike Crapo.) Crapo’s term will now expire at the Date Certain.

Now all Senate Classes have 33 seats, so Congress now puts all Senate seats into the bingo roller—except Idaho’s remaining Class 1 seat, since Idaho already lost its seat. It picks another. It’s Cory Booker, New Jersey’s Class 2 senator!

Class 1 and Class 3 now have 33 seats, and Class 2 has 32 seats. Congress now randomly selects between all Class 1 and Class 2 seats, excluding the seats from New Jersey or Idaho.

…and so on. Repeat until each state has lost one seat, leaving behind Senate class sizes of 17, 17, and 16.

Each state has now had one senate seat designated for elimination, but still has two senators. Each state now holds an election between those two senators to determine who gets to serve out the remainder of that seat’s term, and who is going home immediately.

This election follows whatever rules are currently prescribed by the Constitution: popular vote under the current Constitution; election by the state senate under the proposed Amendment XXXIV. (If a state fails to hold and certify an election like this in time, the senator who currently holds the non-eliminated seat remains in place until the election is held and resolved. If one of them dies between ratification and this special election, he still appears on the ballot, and creates a vacancy if he wins—similar to the Senate election in Missouri in 2000.)

When the Date Certain is reached, the terminated seats are simultaneously terminated, and the survivor in each state finishes out the term of the surviving seat.

However, Congress could easily vary the implementation details in various perfectly reasonable ways. Attempts to juke it would likely trigger messy litigation based on the “as randomly as possible” clause and probably fail in the end, so will, I think, be avoided.

Oh, as for examples of other cases where the Constitution leaves certain crucial implementation details to Congress: Article I, Section 2 orders a census “in such Manner as they shall by Law direct”; Article IV, Section 1 says that Congress will work out the details of proving “full faith and credit”; Article V leaves it to Congress to write all the details of a call to convention; and so on and so forth.

For those readers who read my previous Senate proposal and are curious about exactly why I changed certain details, I explain several in this footnote.

Obviously, I have split the whole thing into two amendments, so Section Six and the first half of Section One are no longer in this one.

Section One (election by state senates) has been slightly adjusted to address some of the evasive maneuvers suggested in the comments of both Part II and Part III. For example, it no longer accidentally outlaws legislation by direct democratic initiative!

Section Two (the consensus election stage) is unaltered. I don’t think anyone really objected to it. Everyone’s concerns were (rightly) focused on the messier contingent election stage.

Of course, Section Three (the contingent election if consensus election fails), is the big one. It was always the problem section. Its existence caused many of the other complications in the proposal. Therefore, it has been gutted and rewritten. The hated DW-NOMINATE is gone. I’ll talk about that in the main body of the article.

I have jettisoned the original Section Four, which provided a fast-track process for the House of Representatives to amend portions of this amendment, partly because that process could, in theory, be exploited to do terrific damage to the rest of the Constitution. It was suggested that, at a minimum, I should add a single-subject limit, but I’ve seen state litigation over single-subject limits, and they are a mess, best avoided.

However, I deleted Section Four mostly because the reason I proposed a fast-track amendment process for this amendment in the first place was because I didn’t have great confidence in the election method I had proposed. I thought it might very well need modification. I feel much better about this one.

Section Five (barring oaths, pledges, and instructions) has been renumbered as Section Four and slightly tweaked to prevent states from putting state senators in the morally compromised position of being forced to swear a state oath that is federally nullified.

I have also deleted Section Seven, making the amendment fully subject to the jurisdiction of federal courts. This provision partly repealed Article I, Section 5, Clause 1, which makes each house of Congress the sole judge of the elections, returns, and qualifications of its own members. Originally, I included this because I have seen how partisan actors vie to break the law in clever ways so they technically can’t be challenged in court, and I didn’t want to let them get away with it.

However, on further reflection (read: reading all your comments), it was put before my mind that the whole point of this amendment is to depolarize the Senate and make it less of a partisan actor. If we succeed, then the revitalized Senate can actually be trusted to perform this function fairly! On the other hand, if we fail, this provision won’t matter, because it would only exist to defend a reality we will have failed to establish in the first place.

You may think the members of the House should also have “due acquaintance with… legislation,” but Federalist 62 expressly disclaims this:

Another defect to be supplied by a senate lies in a want of due acquaintance with the objects and principles of legislation. It is not possible that an assembly of men [the House of Representatives] called for the most part from pursuits of a private nature, continued in appointment for a short time, and led by no permanent motive to devote the intervals of public occupation to a study of the laws, the affairs, and the comprehensive interests of their country, should, if left wholly to themselves, escape a variety of important errors in the exercise of their legislative trust. It may be affirmed, on the best grounds, that no small share of the present embarrassments of America is to be charged on the blunders of our governments; and that these have proceeded from the heads rather than the hearts of most of the authors of them.

Because the House was to be popularly elected, the Founders expected the House to be, well, dumb! They expected the House, by itself, to make “blunders… proceed[ing] from the[ir] heads rather the[ir] hearts.” The Senate was to correct this.

Needless to say, the Senate does not serve this purpose today.

…fueled in part by the misguided Deadlocks Bill of 1866…

Results are mixed. Did YOU decide how to vote for in the last state senate election based on anything other than the letter next to her name? Few did!

Including many of you lovely readers, based on the comment section in Part II!

In case states try to evade this provision by making up new pseudo-legislative bodies with no powers and labeling them the state senate, the amendment also provides some minimum qualifications for a body to count as a state senate: it must have at least ten members, and its support must be required for a bill to become a law. If a state wants to create a third legislative house along the lines of the House of Lords or a colonial Council of Revision, with just five members and no lawmaking power except an overridable veto, the state is free to do so. That body simply won’t count as the “least numerous branch of the legislature” for the purposes of this amendment, and will therefore not be the one that elects the state’s U.S. senator.

The number ten here is not just a matter of prudence. There are certain dependable properties of the deadlock-resolution mechanism proposed in Section Three of this proposal which break down if there are fewer than 10 members in the state senate.

Section 2. Within thirty calendar days of an imminent or actual vacancy in the state’s Senate seat, the electoral house shall convene to elect a replacement. Upon a motion and a second nominating an eligible candidate, the body shall immediately vote by secret ballot whether to elect that candidate or not. If two-thirds of members present concur, the nominee is elected. If not, the nominee may not be re-nominated for this vacancy under this section, and the mover and seconder may not move or second another motion for this vacancy under this section. If there are no further nominations, or if no U.S. Senator is elected in this way within two calendar days, the body shall proceed to a contingent election under Section Three.

Right now, in our extremely polarized country, about half the states are purple enough to put a minority party in control of at least one-third of the seats. In states like Hawaii, where the Democrats control an impressive 92% of state senate seats, the majority will naturally nominate and elect whoever they please, which is likely to be someone close to the party’s ideological median.

In those cases, though, that’s okay! In states where one party has overwhelming control, the ideological center of the party is quite close to the ideological center of the state! My only regret is that candidates in these states could be nominated by the party primary process and mass democracy. I console myself with the knowledge that party organizations in those states tend to be so strong (practically an adjunct of state government) that primary election competition is largely steered by the central committee and usually rather sedate, without the tumults and seizures of a truly mass political campaign.

Of course, in states like Hawaii or Wyoming, where a single party controls roughly 90% of the seats, the minority party will have no leverage under this requirement. However, that’s okay here, because the ideological center of such a dominant majority party is, in effect, the ideological center of the state.

The minority might very well prefer an empty Senate seat to any senator supported by the majority. They therefore have good incentives to deny the state any representation in the federal senate.

Section 3. In a contingent Senate election, the electoral house shall nominate U.S. Senate candidates by secret ballot, each member’s ballot bearing the name of one eligible person, or the words, “I decline to nominate.” These ballots shall be tabulated in the presence of the entire house. Each eligible person nominated by at least one-tenth of those present shall be a candidate.

The proposal requires voters to write, “I decline to nominate” if they are, for whatever reason, abstaining from nomination. This is for a very boring reason: we need nominating ballots to be secret. If some voters turned in blank ballots without taking even a second to write anything down on their sheets, we would instantly know they cast no nominating ballot. If many legislators did this, those casting nomination ballots would be exposed by the time it took them to write down a name, and could face party discipline, which is exactly what we are trying to help them evade. Forcing everyone to write down something provides some protection to those who are actually writing down names.

This is a pretty edge-case thing to worry about. Since, as we will see, both parties have incentives to maximize nominees anyway, it’s unlikely many people will abstain regardless. Nevertheless, better to have this protection on the books than not.

The cap is somewhat less if the number of seats in your state senate is not evenly divisible by 10. For example, in a 62-person state senate, you need 6.2 nominations to become a candidate, but, of course, there’s no such thing as “0.2 nominations,” so each candidate actually needs 7 nominations. 7 / 62 = 8.85, so a 62-person senate is effectively capped at 8 nominations. This makes no real difference for elections or strategy.

Can nominees refuse nomination under this proposal? Obviously, if they are elected, they can decline election / immediately resign. This creates a new vacancy in the seat, thus restarting the election process. But can a candidate refuse to allow his own name into nomination? On this text, he cannot: “Each eligible person nominated by at least one-tenth of those present shall be a candidate.” No ifs, ands, or buts. The only way a nominee could wriggle out of it is by announcing that he is actually under the age of thirty and/or an insufficiently naturalized foreigner. (Until 2024, he could also get out of it by claiming to be a rebel, but the Supreme Court’s bad decision effectively deleted that provision from the Constitution.)

Of course, before nomination votes are cast, a potential nominee can always put Sherman’s word about to his fellows: “If drafted, I will not run; if nominated, I will not accept; if elected, I will not serve.” This usually works!

I don’t think this is an important provision. This proposal would, I think, work just as well if nominees could refuse candidacy. A nominee’s refusal generally hurts his own party, rather than giving the party an advantage, and wastes strategically precious nominating votes from his allies. On the other hand, it doesn’t seem especially important to explicitly allow refusal, either. For most of American history, political parties contained no provision allowing candidates to refuse nomination. (Thus, Sherman had to insist that he would refuse both nomination and election; they could still make him the nominee even if he didn’t accept it!) The GOP still doesn’t have a provision for refusal in its party rules. The Democrats do (Rule C.4a: “have attached thereto the approval of the candidate”), but I think they only added this in 2024, during the post-Biden chaos, in order to ensure any incipient party civil wars would at least have leadership (and, yes, this helped lock things down for Harris).

The proposal requires all ballots to be fully ranked, with no “bullet ballots.” As I explained in the middle of Part II:

Many ranked-choice voting systems are defeated by a tactic called the “bullet ballot,” where the voter only ranks their top choice, leaving the rest of the ballot blank. This encourages all sorts of tactical mischief that prevents the consensus candidate from being identified. Major-party candidates love when their supporters cast bullet ballots, because they are confident that they won’t be eliminated in early rounds, and bullet ballots lower the majority threshold needed to win in later rounds, magnifying the power of an early lead.

Fortunately, the remedy is simple: make bullet ballots invalid.

You cannot, practically speaking, do this in large general elections, because voters simply don’t follow directions and you’d end up with tons of invalid ballots. However, it’s easy to implement in this election, with fewer than a hundred voters, all well-informed. In fact, many state and local political parties already have rules against bullet ballots in internal elections, so legislators know what a bullet ballot is and are used to not casting them.

In a previous iteration of this proposal, this problem led me to abandon open nominations altogether and replace it with a complicated algorithm called DW-NOMINATE! You, the readers, did not like that.

Section 3 (cont.). Then, the body shall immediately vote by secret, ranked ballot. Any ballot that does not rank all candidates shall be invalid. Each ballot may separately veto up to one candidate. A ballot with more than one veto shall be valid, but all its vetoes shall be deemed void.

Any candidate receiving a total number of vetoes greater than or equal to the number of valid ballots cast divided by seven-tenths the number of candidates shall be deemed eliminated.

Amendments like this are necessarily blind to political parties. That is, we can’t just say, “The minority party gets one veto.” If we did, then a few members of the majority party would immediately split off to form their own, fake party caucus. They would then be “the minority party” (updating local rules as needed), and “steal” the veto. Besides, Nebraska’s Unicameral is officially nonpartisan.

Party-identification stuff simply cannot be managed by constitutional amendment, not least because party identification is so fluid throughout American history. The Constitution must be aware of political parties, but cannot depend on local political parties turning up in any specific configuration.

Well, 6.2, but, since you can’t have fractions of a vote in this system, it is effectively 7.

“Sizable” here means “they control at least a third of the seats.”

I think the carrot is important.

After all, it is possible to set the veto threshold even lower, so that the body has the collective power to veto every candidate but one. (The language for this would be, “Any candidate receiving a total number of vetoes greater than or equal to the number of valid ballots cast divided by one less than the number of candidates shall be deemed eliminated.” The “one less” prevents all candidates from being vetoed.)

This would be functionally very similar to Gilbert’s clarified proposal from the comments on Part III, which used single transferable votes to “elect” every state senator, except one, to an “exclusion panel.” My approach, which uses a single veto rather than full rankings, is pretty nearly functionally equivalent, assuming parties coordinate their vetoes effectively. This is a trade-off, because my approach loses Gilbert’s elegant handling of fractional votes, but avoids the wordiness of explaining the transferable-vote veto process, the bizarre “random selection” effects inherent to Hare voting, and the practical burden of counting ballots that rank the entire state senate (up to sixty-seven people) rather than a limited group of no more than ten nominees.

Either way, though, both Gilbert’s approach and my approach can get us to a place where the body vetoes every nominee except one, who is presumably the “least-hated” candidate and therefore wins. Isn’t this desirable? Aren’t we looking for precisely the most broadly-acceptable candidate, in lieu of whichever nominee the largest party can ram through on a raw majority vote?

The fatal flaw with this—well, no, “fatal flaw” is too strongly put. The difficulty with this comes at the nomination step. The majority party will, in general, be able to nominate and veto more candidates than the minority. If every candidate but one is being vetoed, the majority can reliably veto every candidate put forward by the minority party, and then it effectively controls the list of surviving nominees. It can ensure that its preferred candidate will win simply by putting forward several outrageously less acceptable candidates, leaving the minority with a choice between the majority’s preferred candidate and some lunatic. If, on the other hand, the majority tries a similar tactic, but we can ensure that at least one minority candidate survives to a preference vote, the minority has a chance to make the election between some lunatic and some reasonable compromise candidate, which may very well draw off votes from the majority party to elect the compromise.

Gilbert’s method avoids this problem (to a great extent) by nominating every member of the state senate in the contingent election. If there’s no nomination step, the majority can’t do the first step in this two-step manipulation process. This is a worthy idea, but, as with any voting system, there are trade-offs: mechanically, the ranked-choice ballot is very long and unwieldy to count; tactically, requiring all nominees to come from within the state senate limits possible compromise options from outside the state senate; and, stratelegically, this rule would encourage party primary voters to elect more ideologically extreme candidates in safe seats (as if they needed any more encouragement) as a way of indirectly accomplishing the first step in the two-step anyway. Again, none of these problems are fatal. They’re just problems. My alternative approach has problems of its own, because every election system comes with problems (no exceptions). As we’ll see in the final section, I think Gilbert-style variants with more vetoes are worth considering at an Article V convention.

Two-thirds is just a rule of thumb. In reality, it varies a great deal based on the size of the house, the number of nominees, and the degree of cooperation across parties in coordinating vetoes. The “seven-tenths” rule in the amendment means that, in practice, if all goes exactly right, a chamber with a round number of members and perfect bipartisan coordination could see seven out of ten nominees vetoed, or 70%. In reality, the maximum veto tends to wander around between 57% and 65%, depending on house size and number of nominees. Beyond that, if members refuse to cooperate across party lines (they probably will refuse!), or if parties aren’t maximally disciplined, or make mistakes, the actual veto ratio ends up a little lower.

If the chamber ends up nominating a small, even number of candidates (mainly 2 or 4), the maximum veto will be 50%. In a 4-candidate race, that usually means each party can veto exactly one of the other party’s candidates. However, as we have already seen, the minority party usually has both the power and the incentives to force more nominations than that.

A canny minority will nominate enough sensible moderates to ensure one of them survives the veto round. I suggest nominating the most moderate members of the majority party available, to make the choice as tough as possible on the majority! If the minority fails to do this, then their refusal to compromise may cost them all the leverage this amendment tried to give them. You can bring a donkey to water (or an elephant), but the Constitution can’t make them drink.

Section 3 (cont.). Of remaining candidates, if one candidate defeats all others head-to-head, that candidate shall be elected.

[That sentence is the Condorcet rule. Nice and simple. Everything in the following paragraph describes the tiebreak mechanism, which is only invoked in rare conditions anyway.]

Otherwise, the smallest set of candidates shall be identified, such that each candidate in the set defeats every candidate outside the set head-to-head. The candidate with the fewest highest-ranked votes who is not in that set shall be eliminated. If there is now a single candidate who defeats all others head-to-head, that candidate shall be elected. Otherwise, candidates shall be eliminated in this way until a candidate is elected, eliminating candidates in the set only if all other candidates have already been eliminated. Exact ties shall be broken by lot.

Remember, this was all done on one ballot. Doing it all at once prevents the majority from coordinating between rounds, which would give them more leverage and may allow them to nominate recklessly. This isn't the hell I would die on, but I think it's a better approach than separating the veto and voting rounds into separate ballots.

“Least popular” here means the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes on the ranked ballots. Benham’s method eliminates candidates outside the tie before eliminating any of the candidates involved in the tie (the “Smith set”). This is a form of Hare/Instant Runoff Voting, which is really not much better than drawing lots (the usual method for resolving ties in elections), but it is still somewhat better than drawing lots, so we may as well use it.

One interesting property of this proposed system is that it lacks virtually every mathematical property voting nerds desire in a voting system. Instead, it attempts compromises between most of them. For example, it fails clone immunity, allowing the parties to predictably manipulate outcomes (to some extent) by nominating multiple very similar candidates (or “clones”). This is a big deal, and it’s what causes Bucklin Voting to fail so spectacularly. The proposal makes up for its lack of clone immunity by using vetoes… but the vetoes cause it to fail the Condorcet winner and Smith set criteria! Its inclusion of Hare-IRV tallies as a tiebreak means it fails all kinds of monotonicity criteria. The list of failed properties goes on!

One must, unfortunately, not get hung up on mathematical perfections when dealing with anything as messy and rough-hewn as defining rules for human political struggles.

Some Example Contingent Elections

Imagine the legislators in a legislature were numbered from the most extreme member of the majority to the most extreme member of the minority.

So, in a 45-member state senate, Legislator #1 is the majority’s top extremist, Legislator #45 is the fire-breather for the minority, and Legislator #23 is the median legislator. Further imagine that each legislator has a distinct preference for U.S. Senate candidate, either himself or someone in perfect ideological alignment with him. This is an enormous conceit, but a useful one.

The Normal Election

Consider a 38-person legislature where the majority has 21 seats (55%) and the minority has 17 seats. The median legislators are #20 and #21, the most moderate members of the majority.

The majority naturally prefers #12, the center of the party, but #9 won their party primary and is officially their candidate. The minority prefers #34, which, lol, isn’t going to happen. The majority’s different factions nominate #2, #9, #12, and #19. The minority puts forward #21, #33, and #34.

They vote. With 38 votes and 7 nominees, the veto threshold = 38/(7*0.7) = 7.96, which must round up to 8. With 17 seats, the minority can veto 2 candidates, so they take out #2 and #9. The majority also has 2 vetoes between them, and eliminate both of the extreme candidates, #33 and #34. When the dust settles, the only candidates left standing are #12, #19, and #21. Most of the majority has ranked these #12 > #19 > #21, but #19 secretly ranked herself higher (#19 > #21 > #12) and so did #21 (#21 > #19 > #12). The entire minority ranks #21 > #19 > #12. That means #19 beats all comers: she defeats #12 (20 votes to 19) and beats #21 (21 votes to 18). #19 is the winner.

The majority’s primary winner was defeated, and its internal partisan preference was also defeated. The winner sat very close to the chamber’s true center, in the moderate wing of the majority party. Of course, the outcome depended on two members of that moderate wing deciding to defect, choosing their own self-interest and ideological alignment over party loyalty. It helped that they were in a position where they couldn’t be effectively punished for defecting and they could not be accused of undermining the party’s “official” nominee (who had already been vetoed out).

More Tactical Veto

However, what if, instead of vetoing the more extreme minority-party candidates, the majority had instead decided to use its veto power to nuke the plausible compromises? They might just as easily have vetoed #19 and #21 instead of #33 and #34, leaving the final field #12, #33, and #34. Had they done so, #12 would have very likely won the day; #19 no longer gets to vote for herself, and #33 is probably too extreme for #21, so their votes both go to #12, who beats both #33 and #34 on a party-line 21-18 vote.

For this reason, it is strategically critical for the minority party to use all its available nominations on plausible compromise candidates. If they waste precious nomination slots on vanity candidates who can’t win, the majority can (often) easily flex its muscles to ensure its preferred extremist gets into office.

Majority Party Dominates

Consider a 20-person legislature where the majority has 16 seats (80%). They really should have elected a consensus candidate under Section Two, but failed.

The majority’s preference is for Legislator #9 or his nominee, since #9 is dead center of their caucus. The ideological center of the chamber is very close to that! (It’s Legislator #11.) Because the majority is so large, its center and the true center nearly line up.

The tiny minority would obviously prefer someone like #19, but, recognizing that this will never fly, they instead nominate #16 (a Susan Collins-type moderate) and #13 (who is close to the center but juuuust on their side of it). The majority has tons of nominating power and its various factions nominate #1, #4, #5, #9, #10, #12, #14, and #15.

They vote. With 20 votes and 10 nominees, the veto threshold = 20/(10*0.7) = 2.86. Since no one can cast a fractional vote, this rounds up to 3. The minority has only 4 members, so they can only guarantee one veto. They use it to take out #9, the majority’s preferred candidate. The majority’s partisan flank vetoes the most moderate candidates, #15 and #16. The majority’s moderate flank vetoes the most partisan candidates, #1, #4, and #5. When the dust settles, the only candidates left standing are #10, #12, #13, and #14.

Of those candidates, half the chamber (#1-#11) prefers #10 over all comers, so #10 is elected. The majority party’s preferred pick, #9, did not win (although they had the votes to elect her in the consensus round), but everyone ends up pretty happy: the ultimate winner, #10, sits right between the center of the majority (#9) and the center of the house (#11).

Blockade Backfire

Consider a 1000-person legislature where the majority controls 640 seats (64%). The majority has rallied behind a primary winner who is ideologically aligned with #251, well outside the state’s median and fairly extreme even by party standards. However, the minority implacably refuses to support #251, and the majority refuses to offer an acceptable compromise, so the consensus election fails by just a few dozen votes. They are forced to the contingent election.

In order to prevent the minority from vetoing their first and only preference, the majority nominates #251 alone, aiming to jack up the veto threshold so the minority can’t quite veto him. The minority gets wind of this plan and sees an opportunity to exploit the situation. They rally their voters to nominate #753, #900, and #943. (Since the nomination threshold is 100 and the minority only holds 360 seats, this is the best they can do.) All of these nominees are well outside the state’s median.

They vote. With 1000 votes and just 4 nominees, the veto threshold = 1000/(4*0.7) = 357.14 → 358. That’s still enough for the minority to act, though! The minority unanimously vetoes #251, knocking him out. The majority also only has one veto (because there were way too few nominees), which they expend on #943. Excess members on both sides attempt to veto various other candidates, but can’t reach the threshold. Now the only remaining candidates are #753 and #900. Both are fairly far-out members of the minority. In the Condorcet voting, the majority easily and overwhelmingly elects #753, but their attempt to rig the system in their favor has resulted in an opposition candidate winning instead.

Blockade Successful

However, what if the majority had had just 20 more seats, dominating the chamber 665-335? That falls just short of the two-thirds threshold. In that case, the majority strategy would have worked much better. By nominating #251 alone, while knowing that the minority doesn’t have the votes to nominate more than three nominees of its own, the majority guarantees the veto threshold will be at least 358, which is more seats than the minority controls. Unless the minority can win some support from within the majority, #251 will survive the veto round. The minority’s only chance here is to nominate three reasonably attractive candidates within the majority caucus (perhaps #500, #659, and #550) and hope they can persuade the edges of the majority party that #251 is too extreme for the state. Thanks to the secret ballot, they might well succeed! However, as the chamber tilts very close to the critical two-thirds threshold, the minority party begins to lose its leverage very quickly. This is as it should be, of course, but the cutoff can be pretty sharp.

Partisan Civil War

Consider a 435-member house where the majority party controls 222 seats (51%). However, the majority party is riven by internal conflict and unable to arrive at a consensus candidate, finding themselves divided between #35, #111, and #220. (You might call #35 “Jim Jordan,” but I couldn’t possibly comment.) To protect themselves from premature elimination, the opposite sides of the partisan infighting also nominate #36 and #219.

The minority, amused, nominates their leader, #375, but they do really want to keep #35 out, and they’d love to block #111 as well, so they nominate some attractive centrist types: #223, #222, and (due to a lack of cross-party communication) they also nominate #219.

They vote. With 435 votes and 8 nominees, the veto threshold = 435/(8*0.7) = 77.67 → 78. Both sides have enough juice for two vetoes, but the majority is too busy with its civil war to coordinate effectively. The moderate faction of the majority vetoes #35. The extreme faction vetoes #220. The center of the majority party (your basic conservative types) doesn’t have the numbers or the coordination to veto anything, but scatters their vetoes around to various targets, which could help another faction pull off a veto. Thanks to that assist, the minority (which wasn’t sure whether to veto #35 or #36 and ends up allocating a view vetoes to each) is able to knock out #36 and #111.

This leaves only #219, #220, #222 from the majority party, and #223 and #375 from the minority. #375 gets the first-choice vote from nearly the entire minority, but (of the survivors) is the last choice of the entire majority. It ends up a close race between #219, #220, and #222, all very similar members of the majority party who reside close to the ideological center. Each of them beats #223 and #375 head-to-head thanks to the majority party’s backing, but there are some voting cycles between them, and it ends up effectively tied. Benham’s Method eliminates #223, but this doesn’t break the cycles, so then it eliminates #375. This does break the cycles. #222, the most moderate member of the majority party, wins the contingent election and becomes the next senator from this mysterious state senate that certainly isn’t a stand-in for anything.

…And Millions More!

During the feverish days of exploring this system, I vibe-coded, and then greatly refined, a Python script to simulate elections under it. I’ve uploaded the script to my server as election_sim2.py, where you can download it for yourself.

Execute simply by renaming the file “election_sim2.py” (no “.txt”), installing Python, opening a command prompt or terminal window in the directory where you downloaded the file, and typing “py election_sim2.py”.

Be warned, though: the script currently embeds a lot of assumptions about how political parties will behave. (It also treats the veto as the lowest-ranked preference vote, rather than as a separate document, because that’s the method I was originally considering.)

Because of those assumptions, the moderate candidate nearly always wins. What you will want to investigate, as you play around with it the same way I did for six days, are the weird cases, the outliers where Legislator #3 won or whatever. Why is that happening? Is it because one of the parties made a clear tactical error… or is it because one of the parties has found an inherent weakness in the system that it can exploit to elect extremists? If you embed that behavior into the system, does the majority party suddenly start winning with non-median candidates? I ran millions of sims, and looked at hundreds of them with my eyeballs, and the answer was always “no, one of the parties simply made a tactical error,” but the sim is a very imperfect model, so you should regard it only as a tool for exploring the strengths and weaknesses of the system, not proof that it works as intended.

Section 4. Any pledge, vow, oath, or any other commitment by a Senate elector regarding his votes to nominate or elect a U.S. Senator shall be null, void, and utterly without force from the moment it is made (excepting her oath to this Constitution and her state’s Constitution), and no Senate elector may be compelled to make any such commitment. Any instruction, advice, or requirement laid upon an elector regarding same, outside the provisions of this Constitution, shall be likewise null and void.

Section 5. The seventeenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed. This amendment shall not be so construed as to affect the election or term of any Senator chosen before it becomes valid as part of the Constitution.

Although the other amendment I proposed, shrinking the Senate, may well have that effect! Amendment proposals must be considered independent in case one is passed and the other is not, or they are ratified at very different times.

Great read, as always. Do you plan on crafting an Amendment for the Supreme Court? Like the Legislative and Executive branches, the Judicial branch is in rough shape at the moment, though not quite as bad since they aren't subjected to the ever changing whims of the electorate. I've got a couple thoughts on the matter myself.

The 30% minimum to be included in the sortition is what protects against Senator Bernie Sanders of Ohio. There has to be enough extreme members of the minority party to vote for him in the secret ballot. Which would be basically everyone in the minority party.