A Senate, If You Can Keep It

Some Constitutional Amendments #6, Part I: The Senate is dead. We, the People, were found over the body with the murder weapon: democracy.

Many writers propose constitutional amendments in order to demonstrate their fantasy vision of the perfect regime. In Some Constitutional Amendments, I propose realistic amendments to the Constitution aimed at improving the structure of the U.S. national government, without addressing substantive issues.

Why does the U.S. Senate exist?

Seriously, why? What’s it for?

There’s a fairly popular movement among the intelligentsia to abolish the Senate…and, in our current constitutional schema, they aren’t wrong. We have a lower legislative House, elected directly by the People, in proportion to the People, whose purpose is to represent the People’s current popular will. Then we have an upper legislative body, the Senate, which is… elected directly by the People, but not in any kind of proportion to the People, whose purpose is to represent the People’s popular will, but with longer terms to diminish their democratic responsiveness for some reason? How’s, uh, how’s that working out for us?

This is weird. A lot of abolish-the-Senate talk these days is just the usual partisan complaints about which party currently has a structural advantage in the Senate,1 but they have a point! When we already have one house full of populist demagogues,2 what’s the value-add from putting in a second house of populist demagogues, but malapportioned, less responsive, and somehow even more expensive? It wasn’t a colonial tradition or anything. The Continental Congress was unicameral. So was the Confederation Congress.

And Yet It Cools

There is, of course, a realpolitik answer: small states had enjoyed considerable power in the Continental and Confederation Congresses. Since each colony was considered a peer nation, each colony got one, equal vote, sparse New Hampshire the same as giant Virginia. The House of Representatives, by contrast, was a fully democratic-republican assembly, elected by the People directly in proportion to their population. In this new assembly, Virginia would (after the first census) have so many seats that, by herself, she could steamroll the united opposition of the seven smallest states.3 The small states were, understandably, unwilling to put themselves so abjectly at the mercy of the larger states (or, more cynically, to give up so much unearned power), so they refused.

The Senate, in this telling, became the Constitution’s necessary concession, shedding some democratic purity in exchange for a Constitution that all thirteen colonies could actually support. That tale is true, as far as it goes, and it’s still true today: small states shift their allegiances between the two parties, but their support for the Senate is constant as the Morning Star. They will forever hold the democratic majority of the nation hostage to their special interests, and we can either get used to it, or secede.

This is certainly part of the story, but it isn’t the whole story. After all, the Senate is not simply a mirror image of the House but with equal votes between states. As designed by the Founding Fathers, the Senate has a number of distinctive features: longer terms, smaller numbers, distinctive powers over appointments and treaties, and, above all, in the original Constitution, senators were appointed by state legislators, rather than by voters.

The Senate is modeled upon the British House of Lords, whose purpose is to check, correct, and slow down the work of the more populist House of Commons. It’s just that, instead of being staffed by a bunch of random rich fops of mediocre quality whose great-granddaddies sucked up to the king hard enough, the U.S. Senate would be staffed by the wisest and best of each state, hand-picked by the state legislatures to represent their state at the seat of power.4 While it is true that some Founding Fathers accepted the Senate only reluctantly, even these skeptics made lemonade out of their lemons. Together, the Founders crafted a distinctive role for the Senate in our constitutional order. As the old story goes:

There is a tradition that Jefferson[,] coming home from France, called Washington to account at the breakfast-table for having agreed to a second, and, as Jefferson thought, unnecessary legislative Chamber.

“Why,” asked Washington, “did you just now pour that coffee into your saucer, before drinking?”

“To cool it,” answered Jefferson. “My throat is not made of brass.”

“Even so,” rejoined Washington, “we pour our legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it.”

This story is apocryphal.5 It was known to be dubious from the very moment it appeared in print. However, it so perfectly sums up the Senate’s function that it has taken on a life of its own anyway. I could snow you in with quotes from Federalist 62, the notes of the Constitutional Convention, and the Founders’ correspondence, but the central idea of the Senate is better conveyed by Washington’s (alleged) “cooling saucer” analogy. That’s why your AP US History class probably included the saucer tale, but probably skipped the long-winded Madison quotes like:

The use of the Senate is to consist in its proceeding with more coolness, with more system, & with more wisdom, than the popular branch.

Even the Founders who were profoundly skeptical of the Senate’s giving equal votes to every state (like Madison himself!) were fairly enthusiastic about having a “cooling body” as a counterpoint to the House.

The Senate Considered Boron

In fact, the whole Constitution can be understood as a kind of nuclear power plant.

In a nuclear power plant, one part of the system (the fissile material) generates unimaginable power for next to no cost, a miracle from the heart of the sun. This part of the system is quite small. The rest of the system is a vast apparatus, an order of magnitude larger and more complicated, whose sole purpose is to prevent the powerful material at the system’s heart from getting out of control and killing everyone.

Y’all know I love this video, but I’ll betcha still didn’t expect it to show up here of all places. Ha ha!

The Constitution is the same, only, instead of fissile material, it uses the Will of the People. The democratic will is immensely powerful and works enormous good in the world. There is no greater political force on Earth than a free people, and few that are even half as benevolent. However, as John Adams reminded us in 1814:

Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes[,] exhausts[,] and murders itself. There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide.

The original Constitution harnesses the unimaginable power of the People’s will in exactly one place: the House of Representatives. Virtually everything else in the Constitution, including the Bill of Rights, the independent judiciary, and the co-equal executive branch, is there to provide containment, so that the House doesn’t get carried away and kill us all.

The House is not currently fulfilling its democratic purpose. It is sluggish, slothful, unresponsive to the People, and cares a thousand times more about getting hits on TikTok than maintaining and improving the U.S. Code. This series of articles has already proposed not fewer than four amendments aimed, directly or indrectly, at bolstering the House that, like the humble mitochondrion, it can once again serve as the Powerhouse of Democracy. We have proposed to abolish gerrymandering, grow the House (in part to break the power of monied interests), strengthen the House’s leverage over the Senate through the Origination Clause, and to halt the centuries-long encroachment of the Executive by gelding the veto (or, at the very least, restoring the legislative veto). I am second to none in my support for greater democracy—in the part of our government that is designed for democracy.

The Senate is not that place. The Senate is the first, perhaps the most important, Democracy Meltdown Prevention System. Today, it is not serving that purpose.

How the Senate (Should) Constrain the House

It is a commonplace that, if you want two elected bodies to have different perspectives, or different virtues, you need to give them different electorates. You can have all the theoretical checks and balances in the world, but, if every branch is elected by the same people at the same time, all your checks and balances are meaningless. Every branch elected by the same voters will share the same views, so they won’t want to check and balance each other. That’s especially bad, because these branches will also share all the same virtues… and the same vices.

In the original Constitution, then, the four bodies of the federal government all had their own independent power bases: the House derived its power directly from the People; the Executive from the independent, one-time-use deliberations of the electoral college; the judiciary from America’s meritocracy (the President and Senate); and the Senate from the governments of each State. Each U.S. senator was elected directly by the legislature of their home state. This (as the Founders bragged) gave the states both a stake in the success of the federal government, and a measure of protection against its natural inclination to overreach. State governments, being much closer to their people and their distinctive needs and culture, are usually better qualified to serve them—and much easier for the voters to fire if they fall short. Senate appointment gave state governments direct power to ensure states, not Washington, remained at the forefront of politics. This would contain the House when its nuclear-grade populist energy, inevitably, tried to push past the boundaries of the few powers the Constitution inscribes for it. This protected the even more important, more dynamic populism of state-level democracy.

Selection by state legislature also created opportunities to put a different quality of person in Washington. The members of the House, who would have to run and win popular elections, were foreordained to be great at kissing babies “on the stump,” talented at stoking a crowd, and very good at raising money. They would be loud, passionate bordering on demagogic, and extremely sensitive to the shifting sentiments of the People. However, you can be very good at all these things without actually knowing anything about how to write a law or govern a country! The members of the Senate, by contrast, would need to win the approval of actual sitting legislators, who know a thing or two about lawmaking and governance. They would need to be personally impressive and practically accomplished, but not necessarily loud. Instead of polishing up a red-meat stump speech to wow a crowd of laymen who don’t know one single member of the Supreme Court, would-be senators would need to have extended, free-ranging conversations with other legislators on the issues of the day—and hold their own. These men, insulated from direct political pressure, would be free to make the right decisions, even when the right decision was unpopular.

In this way, the House and Senate could be a great help to one another. The House, more passionate and closer to the People, could help shake the Senate out of easy complacency and force it to face the nation’s problems. The Senate, wiser, calmer, and better-informed, could help shape the House’s impulses into sturdy legislation. Moreover, since the Founders expected this more deliberative breed to take the path to the Senate, the Founders invested the Senate with some of the nation’s most critical deliberative functions: confirming the President’s appointments, ratifying treaties, and trying impeachments.6

It was an elegant design.

So, of course, we blew it up.

The Road to the Seventeenth Amendment

We didn’t blow it up for no reason. Like other parts of the original Constitution, the design of the Senate broke down under the tectonic pressures of American politics.

In 1854, Abraham Lincoln ran for U.S. Senate the old-fashioned way. After the November Illinois legislative elections, he resigned7 his seat in the state legislature. He lobbied fellow legislators. He tried to win endorsements from influential newspapers. He reached out to old contacts and called in favors. His supporters and friends called on their legislative contacts and talked up Abe Lincoln. Months later, in February, the coalition of already-seated anti-slavery8 legislators he’d been courting met and endorsed him shortly before the voting started. Lincoln led the early voting, winning the first ballot 45-41-5-2 (with six stray votes for other candidates), but he needed 51 votes, an absolute majority, to win the seat. After several more rounds of voting, Lincoln’s tally slowly shrank. As James Shields, the pro-slavery9 Democrat, pulled ahead, Lincoln recognized it was over and asked his supporters to rally behind Lyman Trumbull, the anti-slavery Democrat (and future author of the Fourteenth Amendment). Trumbull won on the tenth ballot. This was the Founders’ system, working fine.10

In 1858, Lincoln ran again. However, this time, something happened that, according to Don E. Fehrenbacher,11 “had no precedent in American politics.” The newly-formed Republican Party did not wait until after the election to choose their favored U.S. Senate candidate. Instead, they met five months before the election at a state convention and nominated Lincoln for Senate. Lincoln immediately went on the stump against incumbent Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, making his case directly to the people. This led to the justly famous Lincoln-Douglas debates, which were read (and are read) nationwide, and made the Senate election the central issue in the fall voting. In effect, Lincoln (and Douglas) had turned the Illinois state legislative election into a proxy election for the higher, national office.

Making the Senate seat (in effect) popularly elected, of course, ruined the Founders’ careful design, which had aimed to separate the electorates for U.S. House and U.S. Senate. It also, as collateral damage, killed the state legislative races, since state issues and the qualities of specific candidates in particular districts took a back seat to the national issues presented by the Senate race.

I hasten to add that this election was brilliant, and brilliantly fought. I have no beef with Lincoln over it.12 The first breach in a constitutional system is often excusable. Caesar Augustus was a great emperor; it was his successors who proved the weaknesses of dictatorship. Likewise, the Lincoln-Douglas popular campaign was a diamond in American political history, but its successors ate away the foundations of the first branch of the federal government.

We don’t seem to know exactly how fast the “pre-election endorsement” model spread after Lincoln invented it. A common theme in the Seventeenth Amendment literature is complaints about historians’ neglect of this early period, where Senate elections slowly slipped out of the hands of legislators and into the hands of voters. However, the consensus view is that Lincoln’s innovation was used only sporadically over the next couple of decades, making little real impact until the 1880s, long after Lincoln himself had died.13

Three developments fueled the populist overthrow of the Senate between 1858 and 1913: the deadlocks bill, the increase in the Senate’s size, and, perhaps above all, the rise of machine politics.

In 1866, for the first and only time in history, Congress exercised its Constitutional power over the election of senators and passed a law14 regulating those elections. The bill arose because some states were seeing deadlocks, where factions controlled enough seats to block other candidates, but not enough seats to elect their own. U.S. Senate seats could go empty for months while the state legislature was consumed by in-fighting over the Senate. In late 1865, New Jersey attempted to resolve an electoral deadlock by electing a senator with a mere plurality of the vote, not the customary majority. In 1866, the Senate rejected this election, sent the gentleman home, and passed a law clarifying that United States senators must be elected by an absolute majority. They also wrote regulations to govern the amount of time legislatures had to spend on deadlocked senate elections before moving on to other business, and other provisions intended to encourage state legislatures to carry out senate elections in an orderly and timely manner.

The general consensus seems to be that this did not work. Some sources I have read regard the 1866 bill with indifference, which is the kindest treatment it receives; all others argue that it made the deadlock problem worse. The historical record seems to support that. Deadlocks reportedly became substantially more common after the passage of the bill, and they lasted longer, too. Senate seats that might once have lain vacant for months now sometimes sat vacant for years. Between 1891 and 1905 alone—crucial years that turned public opinion against the old system of Senate elections—there were forty-five Senate seat deadlocks, across twenty states. There were occasional riots over those deadlocks. The People got very sour about deadlocks.

In the years after the deadlocks bill passed, the Senate also grew substantially. The body had been born in 1790 with 26 seats. In 1858, when Lincoln did his thing, it was still a fairly modest 64-person body. Over the next few decades, however, as the Union added states, the Senate expanded: to 86 seats in 1890, and 96 seats in 1913.

By way of comparison, the House of Representatives, the huge, raucous lower house the Founders had envisioned as a counterpoint to the Senate, had only 105 seats after the first Census. By 1913, the Senate was nearly large enough to be the Founding-era House. Even today, only five states have more than 50 seats in their state senates (the largest is Minnesota, with 67 senators), yet our national legislature is double that size!

As James Madison had warned at the constitutional convention:

The use of the Senate is to consist in its proceeding with more coolness, with more system, & with more wisdom, than the popular branch. Enlarge their number and you communicate to them the vices which they are meant to correct. […T]heir weight would be in an inverse ratio to their number. …The more the representatives of the people therefore were multiplied, the more they partook of the infirmities of their constituents, the more liable they became to be divided among themselves either from their own indiscretions or the artifices of the opposite faction, and of course the less capable of fulfilling their trust.

The Senate simply got big, and its culture changed as a result. I am by no means afraid of large legislatures when it serves the ends toward which that legislature is directed, but the Senate, conceived as a distinctively deliberative body, should be small enough to allow every senator ample elbow room to know all his peers fairly well and to deliberate with each one of them.

Lastly, as the nation (and the Senate) grew, national political parties became far more organized, and national issues became far more dominant in local elections. (We live in a similar era of nationalized politics, so this is familiar to us, but it is, historically, somewhat unusual.) As national issues took on more and more importance and parties became better and better coordinated, the hole Abe Lincoln had poked in the dam became a stream, then a flood. In the 1880s, parties increasingly nominated specific candidates (like Lincoln did), or even went a step further: this period saw the advent of party primary elections, where a party’s voters picked a candidate. In some cases, this was purely “advisory,” but party candidates were often pledged to support the winner. Even where parties didn’t nominate specific candidates, machine-politics voters often chose state legislators based on which party they would support in the U.S. Senate election. Thus, elections for state legislature routinely became proxy elections for the federal Senate.

Frustrated at their growing irrelevance in their own elections, state legislatures started looking for ways to transfer the Senate election power away from themselves, in hopes that the People would go back to letting state issues dictate state races.

The dominant turn-of-the-century political theory (which I’m afraid still lingers with us today) held that the People could be trusted better than anyone else with important decisions, because the People were purer, wiser, and better suited to judgment than any smoke-filled room packed with legislators, who were presumptively corrupt. This period saw the rise of all sorts of new populist election models that (according to reformers) would save the nation from corruption and misgovernance forever: voter-initiated ballot measures, recall elections by popular petition, voter repeal of specific laws (“referendum”), and more. Naturally, in this fervor for pure, untempered democracy, Senate primaries proliferated. Soon, however, Oregon thought to go a step further: under the “Oregon Plan,” first adopted in 1904 and strengthened substantially in 1907/1908, the general election included a question to voters about who the next Oregon senator should be. Legislators were honor-bound to support that candidate in the Senate election. Later, they became legally bound as well.

In 1913, the Seventeenth Amendment mandated popular election of senators nationwide. However, by this time, it was something of a fait accompli. Akhil Amar tells us that “more than half the states had already committed themselves to a form of direct election—either the direct-primary approach in one-party states or some version of the Oregon Plan.” The Seventeenth Amendment had probably been inevitable for years, made so by political forces and choices dating back to at least the 1890s.

Did the Seventeenth Amendment Work?

Reformers had three main goals in mind when they passed the Seventeenth Amendment:

End deadlocks

Make state elections about state issues again (not the federal Senate race)

End corruption and get money out of politics

I will start with the third, because I haven’t really discussed it yet. Populist reformers believed the Senate was uniquely corrupt, that the Senate was a “millionaire’s club,” that it was unconscionable that money played such an important role in Senate elections, and—most importantly—that the purifying influence of popular election would cleanse the Senate of these ills. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, in his statement recognizing the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment, made enormous promises:

We will find that instead of having the Senate filled up with the representatives of predatory wealth who use their power to oppose the things that the people love — we will find that the honor of a position in that body will be reserved as a prize with which to reward those who have proven themselves capable of the discharge of public duties and men to be trusted with the people’s interests.

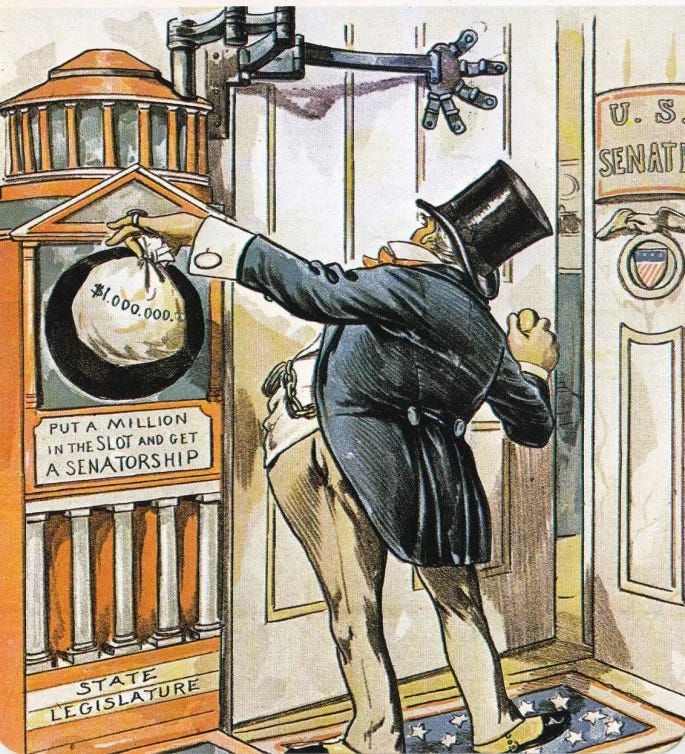

There was never very much evidence for the alleged corruption in the Senate. There was certainly corruption, as there is in all powerful organizations, but it doesn’t appear to have been worse in the unelected Senate as compared to, say, the elected House. Nevertheless, the “unique corruption” story fit the populist zeitgeist of the time. Sometimes, in the right cultural moment, it’s more important for a story to sound true than to be true, and it takes on a life of its own. When William Randolph Hurst, one of the all-time great yellow journalists, realized he could sell newspapers by playing up this angle, he commissioned a series called The Treason of the Senate. The series was largely false and driven by innuendo, but sold a lot of newspapers. In other, similar cases, we look back and label the reaction a “moral panic.” In this one, we label the reaction “Amendment XVII.”

I need hardly tell you that, by forcing Senate candidates to campaign statewide, popular election made Senate elections vastly more expensive, which made the Senate even more of a “millionaire’s club,” made money the most important ingredient of all Senate campaigns, and thus made Senators even more beholden to the special interests than ever before.15 The reformers’ most noble goals for the Seventeenth Amendment backfired spectacularly.

Relatedly, the reformers believed that popularly-elected senators would more meaningfully represent their constituents. Ironically, changing their constituencies from, say, the 148 elected legislators in Michigan to the 10,000,000 people who live there made this completely impossible. As we considered in a previous installment, meaningful representation of a constituency becomes impossible past a certain number of constituents. That number is likely in the neighborhood of 30,000-50,000. Our Congress is badly distorted because each Congressperson has about 20 times that many constituents. But a U.S. Senator from Michigan has 250 times the “maximum” number of constituents. Instead of effectively representing the state legislature (which, one hopes, effectively represents the People), a Senator has no meaningful connection to more than an infinitesimal fraction of his voters (inevitably a grossly unrepresentative sample), and could not possibly have a connection to them no matter how hard he tried. Then we act all surprised when senators “go native” in Washington, and start rumbling about term limits, as if it would somehow help one person represent ten million souls if we fired him and hired someone else.

On the other two points, however, reformers were more successful. Senate deadlocks were indeed abolished. True, we have replaced them with months-long election disputes in the courts, but these long court battles seem both rarer and, for a number of reasons, more acceptable to voters. State elections are still mostly determined by the letter next to one’s name, especially in this era of high polarization. However, that is due to deeper problems with how our Constitution deals with the existence of political parties (or, more accurately, doesn’t). State legislative elections are sometimes kind of like proxy elections for Senate, when there’s a hot Senate race on the ticket that turns partisan voters out to the polls, but there’s no direct connection between them anymore. State legislators seem much freer to run for office on state issues. This is good.

However, the Seventeenth Amendment had other consequences, too.

It is probably not a coincidence that, shortly after the state legislatures lost their ability to police the boundaries of federal power (in order to protect their own), the size, scope, power, and prestige of the federal government exploded. That growth spurt has never stopped. Lots of conservatives blame Woodrow Wilson for that, but Woodrow Wilson has been dead for a hundred years.16 Woodrow Wilson was not a structural change in how our government fundamentally operates. Popular election of senators was.

The Senate has lost most of its deliberative character. To the casual observer, there’s no difference between debates on the Senate floor and debates on the House floor. They’re all demagogues desperate to generate soundbites on C-SPAN and almost none of them have any talent for the actual job of legislating. They’re obstreperous and polarized in a manner that was unthinkable before the Seventeenth Amendment. I will give you just one example: the filibuster. During the reign of the original Senate, the filibuster was on the books and it was sometimes exercised. There was no way to end it, because terminating a filibuster required unanimous consent under the rules of the day. This was manageable, because the Senate had a culture of gentlemanliness that militated against abuses of the ‘buster.

However, in 1917, four years after the Seventeenth Amendment, the Senate found that use of the filibuster had become so abusive that it had to be curtailed. The cloture motion was invented, allowing two-thirds of the Senate to forcibly end debate. Abuses worsened during the Civil Rights era and cloture expanded accordingly. The “routine filibuster” emerged in 1970, and cloture votes, once a rarity, became commonplace. In 1975, the threshold for cloture was dropped from two-thirds to three-fifths, because the Senate no longer trusted that 40% of its number would behave in gentlemanly fashion. In 2005, Democrats pioneered the use of non-talking filibusters against judicial nominees, causing a pitched battle of all-consuming filibusters until, finally, filibusters were completely abolished for Senate nominees. However, in the meantime, Republicans had retaliated by deploying the filibuster against essentially all legislation from the opposite party, a practice Democrats continued when they returned to the minority. In the 118th Congress (2023-24), there were 266 cloture motions, and many more bills with majority support that never even got a cloture vote, because the Democrats knew they wouldn’t win. Filibuster abuse has artificially increased the threshold to pass legislation in the United States to 60% of the Senate, so its days are most certainly numbered. The next Democratic trifecta is already pledged against the filibuster, and the Republicans are restrained only by the small handful of pro-filibuster moderates left in their caucus. A tool to ensure debate continued while all senators were heard—the raison d'etre of a deliberative body—has been whittled and narrowed to the point of imminent extinction, all in response to rampant abuses.

This kind of all-out parliamentary warfare is simply not how the Senate is supposed to work, and it isn’t how the Senate did work for over a hundred years. However, when we deprived the Senate of its distinctive virtues and made senators scrabble for the popular vote like the House, this is exactly the kind of thing one would expect to happen.

The Seventeenth Amendment, though successful at some of its goals, dealt our upper legislative house a mortal blow. It will not recover, and cannot fulfill its noble and useful purpose in our system, until the Seventeenth Amendment is repealed.

However, simply repealing it won’t do. Repeal the Seventeenth Amendment without replacement, and you just invite back all the ills that led to it in the first place. If all you do is put legislative election back into the Constitution, do you think you’d even achieve the goal of getting legislatures to elect their senators? Of course not! Half the states would immediately adopt something like the Oregon Plan, and, without good solutions to the problems that drove us there in the first place, the other half would soon follow.

That’s too bad, because “repeal the Seventeenth” is an easy slogan, and “replace the Seventeenth with a new and untested scheme that honors the original design while addressing its design flaws” doesn’t fit on a bumper sticker.

When Some Constitutional Amendments returns in two weeks, we are nevertheless going to try to give you, the People, an untested scheme that honors the Senate’s original design while addressing its shortcomings. If you’re interested in seeing how this ends, subscribe for free!

(If you’re wondering what happened to this week’s installment of If They’d Made Me Pope, I delayed it for a week out of compassion for those readers who are sick to the teeth of my Catholic-posting, and also because I suspect many readers are going to find the next installment particularly annoying. I’m a good enough blogger not to hide my true opinions, but not so good that I won’t take an excuse to delay!)

The Republicans have held the edge for the last fifteen years at least, and probably will hold the advantage for another fifteen—although their advantage is clearly not insurmountable.

And, I’m sorry, but that is the purpose of the House of Representatives. The purpose of most of the rest of the federal government is to check what the Founders assumed would be the populist mob energy of the House.

Delaware, Rhode Island, Georgia, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and newly-joined Vermont and Kentucky.

This was explicit at the Constitutional Convention, according to the notes of James Madison. John Dickinson was the one who proposed having legislatures appoint the U.S. Senators, and explained:

Mr. Dickinson had two reasons for his motion. 1, because the sense of the States would be better collected through their Governments; than immediately from the people at large; 2. because he wished the Senate to consist of the most distinguished characters, distinguished for their rank in life and their weight of property, and bearing as strong a likeness to the British House of Lords as possible; and he thought such characters more likely to be selected by the State Legislatures, than in any other mode.

A pet peeve: etymologically speaking, “apocryphal” means “doubtful” (or “unknown” or “obscure” or “secret”). It does not mean “fake.”

This comports with the meaning of “Apocrypha” in the Bible: the books of the Apocrypha (and other early Christian writings like First Clement) are disputed as to their accuracy and orthodoxy, not fake. I blame Protestantism for mixing them up following Martin Luther’s propaganda campaign against the Apocrypha. This blame is probably unfair. (You could even call it apocryphal!)

Many people describe a story as “possibly apocryphal” or “probably apocryphal.” This is, properly speaking, an oxymoron. If there is doubt about the origin of a story, then it is apocryphal. If a story is certainly false, then it is simply spurious. The Jefferson-Washington saucer legend is probably false but is still plausibly true. That’s squarely in apocrypha territory.

Yes, I know, people have abused this word enough that the abusive definition has made it into every dictionary, so “probably apocryphal” is not, legally, an oxymoron. It remains morally an oxymoron in my book.

The lack of any special counter-balancing power in the more populist House is a sign of the Founders’ determination to contain the House rather than empower it. It is also something I have tried to correct in this series, because I think the Founders missed the mark when it gave the House nothing.

Technically, he never took it. He was elected to the state house in the 1854 election but gave it up when the election results showed the Anti-Nebraska coalition had enough votes for a shot at electing a senator.

The politics of the 1850s were extraordinarily complex, and calling this particular Illinois state caucus “anti-slavery” paints with rather too broad a brush, which is why I’m expanding on it in a footnote.

Lincoln’s coalition was actually built around opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act which had recently passed Congress. The Act replaced the Missouri Compromise with “popular sovereignty,” whereby voters in each territory would vote on whether to be a slave state or a free state. This led to Nebraska’s admission as a free state; undeclared civil war in Kansas, whose government disintegrated; the destruction of the Whig Party; and, ultimately, the attack on Fort Sumter.

Lincoln himself was far from an abolitionist at this time, but he strenuously opposed allowing slavery to spread outside the territory it already controlled. For him and many slavery moderates, Kansas-Nebraska crossed a red line. Normally, the caucuses that met to nominate Senate candidates would have simply been political parties (Democrats vs. Whigs at the time), but, as the Whigs were in the midst of self-destructing, everything was scrambled, and so the “Anti-Nebraska” caucus met to endorse Lincoln instead.

This label is also overly broad. (See previous footnote.) Shields was pro-Nebraska, but no friend to the slavocrats. He fought for the Union in the War, scored a rare victory against Stonewall Jackson, and now-President Lincoln even sounded him out as a possible commander of the Army of the Potomac while George McClellan infamously foundered. The 1850s were complicated, and politics in the border states rarely cashed out as simply as “pro-slavery” and “anti-slavery.” Still, in 1854, Shields was in the more pro-slavery camp in Illinois politics.

More or less. The Founders, whose great error was their assumption America would have no political parties, or that such a thing was even possible, probably would have been upset at the idea of a pre-election nominating caucus, even a non-binding nomination by a single faction in the legislature. Yet, at that time, the system still basically worked the way the Founders had hoped. In 1858 Illinois, it lurched toward a consensus candidate who, though not my first choice, was nevertheless of the highest quality.

quoted in Akhil Amar, America’s Constitution: A Biography, page 410.

It truly was unprecedented in American politics. No political party had ever attempted to nominate a Senate candidate, even informally, prior to the legislative elections. It was a task that belonged to seated legislators, not to the party faithful nor to the bosses. Lincoln was personally involved in concocting the scheme, as we see in Volume II of the chronology Lincoln Day-by-Day, starting with a letter to O.M. Hatch on 24 March 1854.

However, as Don E. Fehrenbacher explains in his article, “The Origins and Purpose of Lincoln’s ‘House-Divided’ Speech,” this was not simply a case of cynical politicians finding a weakness in the constitutional system and exploiting it for their own gain. As with nearly all of Abe Lincoln’s most shocking legal maneuvers, Lincoln and his colleagues were reacting against enormous pressures. (See generally “The Great Interpreter,” by Michael Stokes Paulsen.) In this case, Fehrenbacher tells us, Lincoln’s Illinois Republicans felt compelled to declare him the Republican Party’s “first and only choice for U.S. Senate” because the seat’s incumbent Democrat, Stephen A. Douglas, had recently won the support and admiration of many anti-slavery Republicans, especially Republican bigwigs “back East.”

This was because Douglas, a great defender of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, had nevertheless waged a searing campaign against accepting the Lecompton Constitution (a basically fraudulent pro-slavery constitution passed by slavocrats in a rigged election in Kansas). This has put Douglas in rebellion against his own party, including President Buchanan. People in the 1850s were no different than people today, so Douglas’s rebellion against the Democrats caused many Republicans to find a “strange new respect” for him. Prominent national Republicans, including even William “Higher Law” Seward and the powerful publisher Horace Greeley, were beginning to pressure Illinois Republicans to endorse Douglas for the Senate seat, despite his continuing support for the Kansas-Nebraska Act and popular sovereignty! The Illinois Republicans realized that their candidates and supporters were unlikely to maintain a united front against Douglas without issuing a clear statement of unity posthaste.

I am aware of no evidence that they realized at the time that what they were setting in motion would be the single largest (and, in my view, most corrosive) structural change the U.S. Constitution has ever undergone. They were just trying to fend off Douglas-lovers and protect the Republican Party’s core position of restricting the spread of slavery. Indeed, under the circumstances, it is unclear that anyone could have stopped something like this from happening in 1858 Illinois, even if they’d wanted to. The shocking state convention was preceded by a series of perfectly ordinary county conventions, many of which also endorsed Lincoln with all the passion the grassroots could bring to bear.

I also suspect, but cannot prove, that the Seventeenth Amendment would have happened with or without the 1858 Senate election in Illinois.

I can tell you that Massachusetts used the Lincoln Maneuver to protect Sen. Charles Sumner in 1862, because George Haynes reports this in The Election of Senators (1906), pp133-134, and in 1868, because Riker (see below) reports it.

I can also tell you that, after the special circumstances of 1858, Illinois did not use it again until 1891. Wendy Schiller and Charles Stewart III say so in Electing the Senate: Indirect Democracy Before the Seventeenth Amendment (2014), in the middle of Chapter 4. (My electronic copy from the library does not include proper page numbers.)

William H. Riker’s seminal work, “The Senate and American Federalism” (American Political Science Review 49 (1955): 452-69) claims that using state legislative elections as de facto U.S. Senate elections was fairly commonplace by the mid-nineteenth century, citing an 1834 Mississippi race as the first example of a practice he claims rapidly normalized. Because his work was seminal, this claim circulated far and wide, including into the pages of De Civitate.

Schiller & Stewart’s 2014 review of his work (in their book cited above) very politely calls Riker’s claim tommyrot. However, they fail to provide a comprehensive review of their own, and they don’t respond directly to some of Riker’s evidence. Their earlier work in “Party Control and Legislator Loyalty in Senate Elections Before the Adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment” (2004) indicates that pre-election party conventions played little to no role in the Senate politics of Florida and New York during the studied years, for whatever that’s worth.

Schiller & Stewart convinced me, and I will have to issue a correction to my earlier De Civ work that relied indirectly on Riker’s judgment. Too bad, too. “William H. Riker” is a great name. Sounds Canadian.

One clarification before we move on: Schiller and Stewart show that specific candidates were not typically chosen by the people, even indirectly, until the 1890s. However, they admit that, with the rise of machine politics especially, state legislative elections did increasingly become proxy battles over which party would control the Senate election process. That is, voters would vote for their legislators based solely on the letter next to their names, based solely on the party’s national platform, even without knowing who specifically the party would choose as senator.

The rise of these proxy battles still provides significant weight to David Schleicher’s thesis (in The Seventeenth Amendment and Federalism in an Age of National Political Parties) that legislatures supported the 17th Amendment largely because they were sick of being drawn into these fights. However, contra Riker, these proxy battles do not appear to have been commonplace until the 1880s. On the other hand, contra Schiller and Stewart, there appear to have been some precedents other than the 1858 Illinois Senate race.

An Act to regulate the Times and Manner of holding Elections for Senators in Congress of 25 July 1866, available in Volume 14 of the U.S. Statutes at Large, Chapter 245 (pp243-244).

It is worth noting that Congress was working on the deadlocks bill at almost the same time as they were drafting the 14th Amendment (sent to the states June 13) and managing Reconstruction. This tells us two things: first, that Congress considered the deadlocks problem so important it couldn’t wait even a year. Second, that they may not have had the bandwidth to fully consider the bill’s unintended consequences, which may help explain why the bill backfired.

Even by 1938, George Haynes was able to show how the Seventeenth Amendment, designed to get money out of politics, had actually poured huge amounts of money into politics. As with most things Senate-related, it’s gotten a lot worse since 1938.

Indeed, Wilson was effectively dead for his last two years in the White House! He and Joe Biden should compare notes, wherever they end up.

The "cooling saucer" story might not be real, but one that almost certainly is real is the description of the Senate of Canada as "ha[ving] the sober second-thought":

https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/files/pdf/MLIConfederationSeries_MacdonaldSpeechF_Web.pdf

(What may be apocryphal about this is that Sir John A. Macdonald's use of the term "sober" was due to his being a notorious drunkard; he reportedly often showed up to the House completely sloshed, especially when in opposition in the mid-1870s when turfed out of power following the Pacific Scandal. Another possibly apocryphal tale is that Macdonald told Thomas D'Arcy McGee that since the Government could not have two drunkards, McGee would have to give up alcohol.)

While the Senate of Canada has near co-equal power with the House on paper (s. 53 of the Constitution Act, 1867 is one of the few limits), any attempt to actually exercise this power would result in popular demand for some sort of broad reform. Senators know full well that their role is to check the worst democratic excesses of the House, not to defeat legislation outright (this does not stop poison-pill amendments), and that stepping beyond this without very good reason will lead to calls for abolition (one major party supports this for self-serving reasons), or democratic legitimisation, generally through direct election (another major party supports this for self-serving reasons; the third major party tends to support the status quo for self-serving reasons) or maybe, if they are very lucky, only something like the Parliament Act 1911 (which almost nobody advocates for because, one, nobody knows about it, two, a comparatively modest reform of that sort would not sate the desire for democracy these days, and three, it doesn't serve the interests of any major partisan faction).

(Actually enacting any of these would be very difficult: https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/13614/index.do )

Consequently they play a delicate balancing act by attempting to ensure that any amendments that make it into legislation that actually passes are ones that are good and useful and generally not controversial, and that they don't actually block the House's legislation without extremely good reason. (To the point where the government will sometimes use the fact that the Senate has a legally separate legislative process to slip in provisions that they should have included in the version presented to the Commons but were precluded by procedural rules from adding later once this became apparent.)

(The monarch plays a similar balancing act, staying out of the way of democratic processes right up until only monarchical intervention can keep said processes functioning normally, with the possibility of monarchical intervention serving to keep political actors from straying outside the bounds of said processes. I think it no mistake that the model of parliamentary constitutional monarchy, in some form, has produced as many stable, more or less liberal democracies as it has while republican models, especially those founded on the US model, have proved far more brittle. One need only look at the history of democratic governance in Latin America to see this, though admittedly there are other factors at play there as well.)

As for the fast-moving democratic paroxysms to which parliamentary systems are sometimes subject, keep in mind that partisan electoral politics is a check on that! In majoritarian electoral systems, any legislation that is too odious to the opposition will be repealed once they take power (unless you stay in power long enough that it just becomes an accepted part of life and too much else is built around it to make it possible to repeal cleanly); this does have the effect sometimes observed that the first year or two of a new government is spent repealing all the previous government's most odious legislation rather than doing anything substantively new. In proportional systems, since most governments will be coalitions of some sort, it is often the case that each successive coalition will have some overlap with the previous (New Zealand may be an exception to this for assorted reasons), and consequently cannot fully repudiate the previous government's policies, which in turn means that any policy a government wishes to enact cannot be wholly opposed by whoever happens to be in opposition at the time, lest it be impossible to form a coalition following the next election. If the electorate agrees that the "parade of horribles" is truly horrible, then whoever takes power next will be able to move just as quickly to repeal it all as the enacting government was able to move to implement it.

I am, of course, interested to see whatever you do propose, but my inclination (which is, of course, influenced by the constitutional tradition I learned) is that these sorts of implicit checks serve to protect counter-democratic institutions much better than explicit, entrenched textual provisions ever could. (For instance, outside of a Corwin Amendment-style provision banning any amendment that would restore direct election of Senators, I am very curious to see how you propose to keep the People from, at least at some point, demanding that the democratic reins be handed back to them--or convincing them to give it up in the first place.)

I think making the U.S. Senate function like the German Bundesrat would fix the problems. James, have you looked at how the Bundesrat works? It seems to work well to present the voices of the different German states in the German parliament.