Worthy Reads: Prepping Your Phone for the Thanksgiving Postprandial Doomscroll

Worthy Reads for November 2025

Welcome to Worthy Reads, where I share some links that I think are worth your time. Everyone gets half of this month’s items (and some thoughts to chew on), but the other half (and footnotes) are paywalled. The paylisters keep me writing, though, and deserve a treat.

“Officers at Common Law,” by Nathaniel Donahue:

The Framers of the federal Constitution said almost nothing about how subordinate officers would be held accountable. This Article provides one overlooked explanation for this longstanding puzzle. The Constitution was enacted against a well-defined jurisprudence that has largely fallen from view: a law of officers. When using the term “Officer” and its framework of “Duties,” the Constitution invoked a distinctive method of regulating state power, in which officers were personally responsible—and liable—for discharging duties defined by law. The Framers and Ratifiers of the Constitution expected that these common-law rules would fill the gap left by the document’s silence.

This Article weaves together the strands of statutory and common law that constituted and regulated the early American officer. This system of legal organization, drawn from longstanding English and colonial practice, empowered officers to create a decentralized governing apparatus that blurred the line between public and private. Its regime of harsh personal liability and individual empowerment impeded efforts to construct a top-down hierarchy by empowering and encouraging officers to resist orders from their superiors. As Americans developed a bureaucratic state over the nineteenth- and twentieth centuries, judges and lawmakers replaced this officer-based paradigm of governance with a system of administrative law that was more conducive to the modern state.

It’s been way too long since I posted a law paper in Worthy Reads, and this is a good one to break the fast.

In its own right, this article held my attention. Perhaps I have been “officer-pilled”! During the insurrection court cases, I became deeply invested in the original meaning of “officer of the United States,” and maybe I’m the only one who got stuck on it.

I don’t think that’s it, though. One of my favorite little books to pull off the virtual shelf and read for a few minutes1 is David Friedman’s Legal Systems Very Different From Our Own, which wonderfully highlights how many different ways there are to structure judicial power outside the Anglo-American tradition. All legal systems share certain things in common, but different design choices and different social capacities can lead into unrecognizable territory.

Donahue’s “Officers at Common Law” paints a picture of a legal regime very unlike our own… except, this legal system is our legal system! It’s in the Anglo-American tradition! It’s less than two hundred years old! It’s like he’s woken up and discovered Tartaria!

Did you know that, once upon a time, in many states, if the Surveyor of Highways didn’t plow the snow from your road on time as the law required, you could sue him for damages? That state employees sometimes had to post bond upon assuming their duties, a deposit in case they broke the law and their boss was held personally liable? Did you know that George Washington believed that he was powerless to fire deputies of the Postmaster General, even if he thought they were bad at their jobs, because only the Postmaster General himself had authority over them?

It was a different world! The article takes a long time to get rolling, but, eventually, fleshes out how that world worked. I thought it was neat.

It is also interesting, of course, because, the leading theory of executive-branch authority among constitutional conservatives today is the unitary executive theory, which holds that the Constitution vests executive power in the President exclusively, and so the President has an inherent right to direct the actions of every member of the executive branch. This theory—which, cards on the table, I have believed in for a long while—has been a key part of many lawsuits involving Mr. Trump’s attempts to reshape the White House by firing people (including people at the Fed). If this paper is right, then unitary executive theory is wrong, at least for originalist-textualists like me. It may still be the case that the President has an inherent removal power, and that Humphrey’s Executor is therefore still wrong, but this paper attempts to put the torch to the notion that the chief executive had exclusive, comprehensive executive power (and puts the removal thesis under serious strain).

Now, I don’t change my whole view on the basis of a single paper’s presentation of historical evidence that may, for all I know, be hotly contested. I don’t think Seth Barrett Tillman has written anything about this, but I’m pretty interested in what he might say. You should certainly regard papers released the same term as major Supreme Court cases dealing with the same subject with some initial suspicion. But, honestly, even if the whole thing were fiction (which seems very unlikely), it would still be a fun read, just for the picture it paints of a very different way of thinking about government officials.

Frankly, wouldn’t it be great to be able to sue Mayor Melvin Carter of the City of Saint Paul—not the city, but Mayor Melvin personally—for his abject failure to plow the roads in a timely fashion? Doesn’t modern administrative law, and the administrative state it supports, kind of, well… suck? Even for those of us (including me) who think Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales was correctly decided under the law, don’t we all pretty much agree that the outcome stinks for the poor dead kids? All these questions are opened anew by this paper. I commend it.

“Using ChatGPT is not bad for the environment - a cheat sheet,” by Andy Masley:

When you add all these, the full CO2 emissions caused by a ChatGPT prompt comes out to 0.28 g CO2. For context, this is the same amount of CO2 emitted by:

Streaming a video for 35 seconds

Uploading 9 photos to social media

Driving a sedan at a consistent speed for 4 feet

Running a space heater for 0.7 seconds

Printing a fifth of a page of a physical book

Using a laptop for 1 minute. If you’re reading this on a laptop and spend 20 minutes reading the full post, you will have used as much energy as 20 ChatGPT prompts. ChatGPT could write this blog post using less energy than you use to read it!

This is the gist of it. The balance of the article runs through rebuttals. (For example, “What about water use?”) Indeed, it seemed to me, by the end that there was no rational environmental case against AI at all (YMMV), unless:

you are the sort of strong environmentalist who doesn’t own a car or a television because it’s bad for the environment, or

you are opposing one specific data center in your specific backyard because of site-specific environmental issues. Of course, in this case, your beef isn’t really with AI, but with America’s immense appetite for data of all kinds (of which AI represents only a modest fraction), and specifically with how that appetite is manifesting vis-à-vis your backyard. Still, this objection is legit. I’ll allow it.

Given that the environmental case against AI doesn’t exist (or, if it does exist, it must be very esoteric), it is interesting that so many people repeat this criticism, and it bears wondering why people do that.

You want my theory? (I hope so. You’re subscribed to my newsletter. Only a very small number of you were judicially sentenced to subscribe to De Civ as part of a plea bargain.) I think people get hung up on the environmental arguments against AI for the same reason that they get hung up on continuity arguments against certain movies and TV shows.

Take Star Trek Picard. (Please!) I’m not going to get deep into media criticism here, but Star Trek Picard is a disastrous car wreck of a television show at every level. Each season is uniquely and distinctly the worst thing Star Trek has ever done.2 At its highest highs, Picard is not nearly as entertaining, as engaging, or as humane as the first season of Farscape, a forgettable, no-budget show the SciFi Channel used as filler in the early aughts3. Picard’s seasonal arcs are the kind of writing you’d expect to read on the back of a breakfast cereal, its episode-to-episode execution wildly inconsistent and unhelpful, its original characters obnoxious, and its “legacy” characters bear no resemblance to their originals (which rather misses the point of including them). Character arcs meander and rarely make any sense, then get pruned and replaced with new character arcs that do the same thing. There is almost nothing satisfying about watching Star Trek Picard, and almost infinite problems to complain about.

Yet, when fans actually go to complain about Picard, they talk surprisingly rarely about (say) Q’s nonsensical plan in Season 2, or its hamfisted rewriting of Jean-Luc Picard to fit The Trauma Plot. Instead, they complain about Picard’s sins against the broader Star Trek continuity:

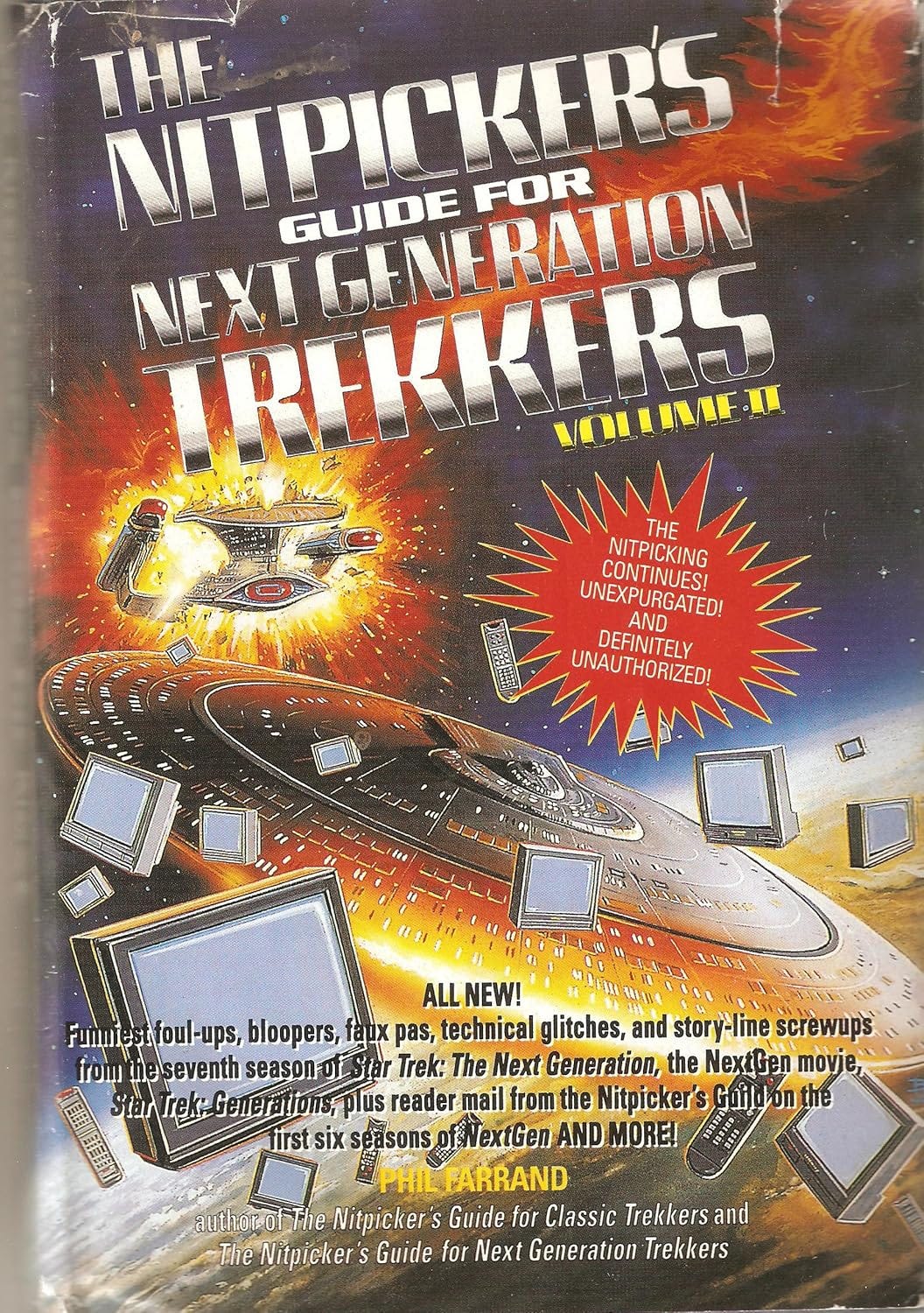

I don’t mean to pick on YouTube’s MajorGrin here; I enjoy his work. This is just a very odd critique to make. They’re not wrong, and continuity is very important (because of its role in verisimilitude and, ultimately, sub-creation), but these kinds of continuity errors are endemic to all large television universes, including Star Trek. I owned this book as a child:

It was 407 pages long. The social contract between writers and audiences is that writers agree to do their best to maintain a consistent continuity, and the audience agrees to forgive and (more importantly) forget the occasional screw-up. When the show is good, they do! When the show is bad, they don’t.

I don’t think most people are well-equipped for literary criticism. It is not easy to articulate exactly why it’s so stupid and awful to, say, turn the beloved learning-to-be-human character from a previous series into a revenge-driven mass murderer with a chip on her shoulder about humanity’s racism. However, it is very, very easy to point out how Series VII, Season 1, Episode 2 contained a line that contradicted a throwaway line in Series II, Season 3, Episode 10.

I think that, when people dislike something, they may not be able to understand or articulate why they disliked it. When that happens, they will resort to the strongest argument they do understand. In the case of television and movies, that’s very often continuity.

In the case of LLMs, it’s environmental impact. It’s a bad argument—in fact, a much worse argument than continuity—but it’s easy to understand, and it’s powerful (because people feel strongly about protecting the environment), so that’s what they go with. They likely have deeper fears about job losses, the displacement of humans from artistic creation (hitherto the most uniquely human activity), the destruction of human relationships, and the construction of Paul Kingsnorth’s Machine. These fears are strongly felt but hard to articulate, very debatable, and (in our technophilic era) can make one sound like a Troglodyte kook calling for Butlerian Jihad. So they say, “ChatGPT is destroying the planet,” instead. Even though it isn’t.

“An Inside View of Hoity-Toity East Coast Boarding Schools,” by Nephew Jonathan:

There are, of course, two ways of balancing your books: you can cut expenses or you can increase revenue.

Scenario: it’s 2009;

$French_teacherat$Schoolhas trouble getting$Studentto learn the days of the week in order. They do flashcards. He asks her to recite them in English.She can’t.

$Student’s parentswere paying full freight for her, and it was 2009 so the endowment had just taken a once-in-a-lifetime beating. In 2005 or 2018$Studentgets rejected; in 2009 she gets admitted.This doesn’t necessarily put a huge dent in the school’s reputation unless it becomes a pattern (particularly in a scenario like the Great Recession when everybody is in the same boat). Unfortunately at

$Schoolit did.$Schoolnow costs over $60K a year and doesn’t offer AP classes. A more diplomatic way of putting it (this is a boarding school, we’re learning to be diplomatic) is that$Schoolended up in a different market niche.

I know nothing of boarding schools, and this article was just a fascinating explanation of them. What is their purpose? How do they work? Why do they work? This is just a good read about them. It has nothing to do with anything at a larger cultural level. It’s just an anthropological dive into a different culture.

Anyone who has ever attended or, better yet, worked at an American private college will recognize not just the conclusions he draws about admins, but even some of the specific character archetypes. I sure know that my college was kept afloat, in part, by rich Saudi kids paying full freight (and freezing their butts off in the Minnesota winter) while the rest of us got various tuition subsidies.

“The Goon Squad,” by Daniel Kolitz:

So where were the gooners? A few seconds’ research revealed their home base: Discord, a social messaging platform not unlike Slack, offering a multiverse of chat-room servers accessible by invitation. If Instagram was where millennials went to post infographics about racial disparities in income and policing, Discord was where zoomers went to swap the screeds of lesser-known school shooters. Or to talk about gaming. Or whatever zoomers did. This was supposedly where the online youth were headed: away from their parents’ social platforms into private, self-policed spaces, little islands of affinity. I joined the first relevant server I could find: the GoonVerse, which had more than fifty thousand members. I examined the rules, which were at once surprisingly woke (no hate speech, no misgendering) and strict enough regarding the posting of child pornography as to suggest a serious and recurrent problem. Before entering, I was prompted to choose my “roles.” Age, region, and gender I could make sense of, but things grew confusing from there. Did I want to be “pinged for tournaments”? Was I a “hentai wankbattler,” or merely a “regular wankbattler”? These questions I answered at random, and then I entered the “stream room.”

Picture this: you work for a masturbation factory in hell. You log on to your scheduled workplace Zoom call.

From one perspective (the ordinary, pedestrian perspective), this is an interesting anthropological deep dive into people who have simply taken a virtue—masturbation—to excess. All things in moderation, people! This is, no doubt, the mindset of the Harper’s audience who first gawked at it.

Of course, I think most people my age are already familiar with the gooners in broad strokes (sorry!), so this story isn’t shocking to us like it is to the article’s original audience. (I assume the average Harper’s reader is 71 years old and has only ever viewed pornography in magazines or DVDs.)4 Even so, the full horrors are still good for a little concerned gawking. It’s like that TV show Hoarders. Everyone knew what they were going to see, but they watched anyway for the cringe. This story is that, but for masturbation freaks. The more people see this, the more they will support laws that put pornography behind an age gate, and that’s good. (These laws are already quite popular.)

On the other hand, from another perspective (mine), this is an anthropological deep dive into the throbbing mass (sorry!) at the center of our culture, because masturbation is the arch-vice of our society.

First, we endorsed masturbation. This happened over the course of the early twentieth century, culminating in the Sexual Revolution. It happened for understandable reasons. It was an overdue backlash against the insane medical hysteria over masturbation that had seized Europe with the publication of Onania and Tissot’s L’Onanisme in the early eighteenth century. This public panic lasted into the late nineteenth century, when Sylvester Graham invented his eponymous Graham cracker to help fight masturbation, and one of Graham’s disciples, John Kellogg (of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes fame) endorsed mass male circumcision in order to “cure” masturbation. Eventually, the world (correctly) realized that masturbation will not actually kill you… then swung the pendulum far in the other direction, on equally worthless medical “evidence,” to the point of positively encouraging it. (No, masturbation is not going to stop you from getting prostate cancer. Sorry. You’ve been lied to.) By the year 2000, we had a firm grip (sorry) on our old “prejudices” and were now firmly pro-masturbation.

This was survivable.

Then, as Kolitz puts it, “in the span of about five years earlier this century, virtually every child in the developed world was granted instant, unrestricted access not merely to hardcore pornography but to some of the most extreme examples of it ever produced in human history.” Much of the productive capacity of the human species—probably more than ever in history—is now devoted to the production and consumption of base sexual fantasy. Dark Satanic mills worth billions of dollars feed women into a machine that churns out #content in order to keep men in a docile, glazed stupor, consumed by sexual fantasy which they know isn’t fulfilling, which they know only fuels their own despair, and yet unable to look away. They’d look just like stunned sheep if it weren’t for the fist in their laps.5

This vice has, of course, many terrible effects directly. The immediate human wreckage is ubiquitous, but this article shows it at such a grotesque extreme that even those inured to it might be able to see it.6 What it does to the dating market is alarming at a macro level and terribly sad at the micro level, and this hardly scratches the surface of its direct effects.

However, our society’s acceptance of PornMasturbationOrgasm—nay, glorification of it—seeps into everything else, too, indirectly. What I particularly like about this article is that it glimpses this reality. Just one facet of it (social media), but he sees it. I’ve also written about how masturbation is the fundamental idiom of current popular film. Who are we to tell them to stop? If pursuing pure animal pleasure, unconnected from growth or goodness, is a worthy (or even acceptable) human aim, then why should our art, or our rhetoric, or anything else aspire to anything more? Your friends on Facebook who relentlessly ragepost memes about incipient socialism, or Trump’s coming coup, are just doing it for the dopamine hit. They’re masturbating. Those of us who seek out only the news media we like and agree with, letting it fill our souls with whatever emotion feels good: masturbating.

…I couldn’t ask for a better segue to Heather Cox Richardson and (sigh) Tucker Carlson: