If They'd Made Me Pope: Fast Fast Fixes

Restoring the ancient disciplines

Several years ago, I visited a Dominican friend of mine who was being ordained to the transitional diaconate in Washington, D.C.. When I jokingly mentioned that either one of us could be elected pope, he laughed right in my face and said I would be a terrible pope. (He added that so would he.) My friend was right, of course, but it still got me thinking harder: what makes a good pope? What should a pope actually do?

Now we have a new pope, so, on the off chance Pope Leo XIV is browsing De Civ looking for ideas, this ongoing series says what I’d do If They’d Made Me Pope.

Straddling the border between Catholicism’s immutable, divine doctrines and its messy, fluctuating human governance, we find the disciplines, which are a little bit of both.

Catholic disciplines strike close to the heart of Catholic life, in a way that (for example) the formal process for investigating a possible saint doesn’t. As such, many (all?) of the disciplines are grounded in Scripture or very ancient practice. The details have evolved over time through a complex interplay of local customs, universal customs, codified rubrics, and actual canon law.

However, the disciplines form much of the warp and woof of daily Catholic life. Even though they can change, actually changing them feels like a revolution.

For example, everyone in the world knows that Catholics don’t eat meat on Fridays in Lent. This is so well-known that there’s a common story that McDonald’s introduced the Filet-o-Fish sandwich during Lent so that they could continue to sell sandwiches to Catholics during those six weeks.

The story is mostly true. Lou Groen, a Catholic in a 90% Catholic neighborhood, owned a Cleveland McDonald’s and was getting destroyed on Fridays. “Everyone was going down the street on Fridays to Frisch’s restaurant that sold a fish sandwich,” his granddaughter explained. Fridays averaged a measly $75 in sales. Groen talked Ray Kroc into allowing fish onto the menu, which saved his business and created a nationally successful sandwich.

Only Groen didn’t do this in Lent. He was losing his shirt in Winter 1961; he introduced the Filet-o-Fish on February 13, 1962. Lent that year didn’t start until March 8. So why is Groen making bank on fish sandwiches in January?

At the time, the discipline of the Church was that Catholics must abstain from meat on all Fridays of the year, which had been the discipline of the Church from time immemorial. In the early 1960s, the Vatican allowed national churches to vary the rule, so, in 1966, the U.S. National Council of Catholic Bishops (like many other national bishops’ councils) passed legislation that allowed Catholics to do an alternate form of penance on Fridays outside Lent, so (of course) the whole discipline immediately collapsed. Nobody did alternate forms of penance. They just stopped treating Fridays special. In law, the discipline remains. In custom, most Catholics only abstain from meat on Fridays in Lent, and the transition has been so complete that very few people even remember that the practice used to be quite different.

This is both an illustration of what Catholic disciplines are, and a cautionary tale about changing them. Canon law and its obscure legal processes can be changed (relatively) easily. All you have to do is tell the canon lawyers and local bishops what the new law is and make sure they follow it. The disciplines, however, are more of a living thing. To be effective, they must be received by the whole Catholic people. This is hard. They should not change lightly. They cannot change easily. The pope’s legal power to change them is unlimited; his practical power anything but.

How’s that for an intro to a pair of articles about how the pope should change a bunch of Catholic disciplines?1

Restore a Eucharistic Fast

Catholics love our bodies. We love the flesh. God created it all good. However, we are keenly aware that the pleasures of the flesh, though good in themselves, are so loud that they can make it impossible to hear the still, silent voice of God. Jesus Himself fasted frequently, and exhorted His followers to fast prayerfully. The flesh must learn its place.

One place where this is particularly obvious is the Eucharist. Since Christianity’s earliest days, worshippers have fasted from human food and drink for a period of time before receiving the Living Bread in Holy Communion. This gives the recipient time and space to cultivate an appropriately receptive spirit.

Unfortunately, today’s Eucharistic “fast” is a joke. Canon law currently requires a fast from food and drink2 for only one hour before communion. Not before Mass; before communion, which typically occurs 40-50 minutes into Mass. What this boils down to, then, is a “don’t eat during Mass” rule, with a small “no snacks in the car on the ride over” proviso. It is worthless. My grandparents (who were the furthest thing from fanatics) refused to believe that the Church would impose such a ridiculous rule, and, as far as I know, they went to their graves maintaining a fast of one hour before Mass, which was what they assumed the rule must actually be. Meanwhile, other Catholics today often have no idea the rule even exists, or ever existed!

Throughout the second millennium, the Eucharistic fast began at midnight and ran until the Eucharist was consumed. This is confirmed both by Thomas Aquinas and the Council of Trent. Earlier norms varied. (For example, some jurisdictions began the fast at sunset on the previous day.) However, all traditions agreed that the Eucharist ought to be the first thing a Christian consumed on the day of reception.

This worked well for the time, since people were mostly asleep in the middle of the night and Mass began in the morning, so it was effectively a fast of perhaps three to six hours. In the modern era, as I understand it, the dire pastoral constraints imposed by World War II pressured the Church to enable Masses at different times of the day. Once enabled, I guess it was hard to put the genie back in the bottle. However, the midnight-to-Eucharist fast is much more difficult if Eucharist is at 6:00 p.m. instead of 6:00 a.m.! The Church sought an accommodation to enable evening Mass without making the fast onerous.

In 1953, Pope Pius XII offered a “concession,” which mitigated the fasting requirement to just three hours for those attending evening Mass. In 1957 (perhaps finding such selective discipline unworkable), Pius extended the concession universally, but he nevertheless “strongly exhort[ed]” everyone to continue observing the ancient midnight fast. He further insisted:

All those who will make use of these concessions must compensate for the good received by becoming shining examples of a Christian life and principally with works of penance and charity. [sic]

LOL. ROFL, even. My understanding is that everyone used the concession, and nobody felt particularly obligated to become a shining example of Christian life. Sometimes I read things from popes that make me wonder whether they’ve ever actually met a Catholic.

In 1964, shortly after the Second Vatican Council, Pope St. Paul VI shortened Pius’s plausible three hours to today’s single useless hour. To this day, I wonder whether Paul thought he was imposing the requirement my grandparents thought he was imposing (fast for an hour before Mass), but what he signed reduced the Eucharistic fast to an hour before communion, effectively abrogating a universal spiritual practice dating back to before Augustine, and quite possibly all the way to the Apostles.

The argument at the time was that barriers to the Eucharist needed to be torn down, but, if that was true, then surely we have gone too far in the opposite direction. The Church feared a world in which the overscrupulous received only rarely (sometimes as little as once per year!), but we now live in a world where the underscrupulous receive weekly, very often in a state of serious sin, “eating and drinking judgment upon themselves,” as Scripture says. Confessors today must remind penitents that this, too, is a serious sin. Many never hear them, because loads of people in the weekly communion line haven’t been to confession in years (which is also a sin!). The Eucharist should never be fenced off from the faithful, to whom Christ gave it as His greatest gift, but maybe a nice little gate? If nothing else, the midnight Eucharistic fast provided a good excuse to teenage boys who wanked the night before and needed a parent-safe excuse for avoiding the communion line. The one-hour fast is useless for this, requiring the teen in question to perform comical imbecility about ten seconds before getting in the car.3

I do genuinely love and make great use of evening and night Masses, which have thrived thanks to these concessions. One of my favorite Masses in college was the “Last Chance Mass” at the local minor seminary, which was a beautiful little Mass, always packed to the gills, offered at 9:30 p.m.! I am also aware of the danger of imposing disciplines too enthusiastically on a flock that has grown used to their absence. Nevertheless, the Eucharistic fast was good for the flock and good for the Church. We effectively do not have one.

As a result of their decentralized ecclesiology, the modern Eastern Orthodox have a stubborn adherence to received traditions, with minimal accommodations to modernity. In the fasting department, this has served them very well. Current E.O. practice in general is a midnight fast before morning Eucharist and a six-hour fast before any evening Eucharist (but, of course, Orthodoxy’s decentralized ecclesiology admits considerable local variation). Since Catholicism already tried having different rules for morning and evening Masses (and, apparently, it didn’t work), Pope Me would simply impose a universal six-hour fast. For people who sleep until 6:00 a.m. and Mass in the morning, this is functionally the same as a midnight-onward fast, but it makes evening Mass possible.

This would undoubtedly take many years to sink back in. Eighty years in abeyance will make any discipline strange and foreign-feeling, no matter how many thousands of years of life it had before that. Still, we’d get it into the examinations of conscience, we’d have priests preach about it, we’d probably have to sigh write a document explaining it to the world (something my papacy would steadfastly avoid in general). Slowly but surely, this valuable and venerable spiritual practice would return to the West.

Restore Meat-Free Fridays Year-Round

All that stuff I just said, but for the Friday fast.

As I explained in the intro, it is already technically the rule that, on Fridays, Catholics are to either abstain from meat or perform “alternate forms of penance.” The alternate forms of penance did not take root, but everyone abandoned meat abstinence anyway, so, in most of the Catholic world, the rule is now all but forgotten.

I would abolish the alternate form of penance.4 The entire Church would return to meatless Fridays. Kids at school would stop looking at my kid weird when she says she can’t have sausage pizza because it’s Friday. My kids would stop thinking it’s some kind of weird Heaney-family tradition rather than the still-binding universal law of the Church.

This would, again, take time. The U.K. Catholic Church restored meatless Fridays in 2011. A 2021 survey of Catholics in England and Wales showed that, ten years later, about 26% of self-identified Catholics in the U.K. were actually following the new abstinence rule5 and about 41% of U.K. Catholics had at least changed their diets because of the rule.

This is actually pretty good! When surveying Catholics, you must remember that the majority of the surveyed population is not religiously Catholic, but only culturally Catholic, with marginal attachment to the Church. Religious Catholics attend Mass weekly. (Failure to do so is a grave sin.) In the U.K., only 41% of self-identified “Catholics” actually attend Mass at least monthly, and only 31% attend at least weekly.

If we make the reasonable assumption that the overwhelming majority of Catholics who are following the meat-free Friday rule are also weekly Mass-goers, then this survey data shows that a majority of weekly Mass-goers are following the new abstinence rules, only ten years into their implementation!6 Give it another generation or two, and everyone will have forgotten the anomalous years where Catholics ate meat on Friday outside of Lent.

Strengthen the Lenten Fast

All that stuff I just said, but for Lent.

Catholics currently abstain from meat on Fridays in Lent. (In Lent, no alternate form of penance is permitted.) On Ash Wednesday, we are also required to refrain from eating between meals, and to cut back from three regular-sized meals to one regular-sized meal and two small meals. In practice… those two “small meals” typically look pretty regular to me.

Compare this to Eastern Orthodox fasting, which is much closer to the historical norms of the Church. On every weekday in Lent, the Orthodox abstain from both meat and dairy. (Many add oil, fish, wine, and shellfish, at least during Holy Week.) On every weekday in Lent, they eliminate breakfast and reduce the size of lunch and dinner. Of course, the Orthodox place great emphasis on individual spiritual direction. Every source I have seen insists that their fasting rules are ideals for those capable of attaining them, not universally binding laws as in Catholicism. Still and all, they’re beating us on Lenten dietary fasting like Keith Moon on the drums.

On the other hand, communal dietary fasting is not the only kind of fasting there is. Catholics also “give something up for Lent,” such as desserts or video games. This is universally seen as an ordinary Catholic discipline. Nearly all Catholics do it, even those only marginally attached to the Church.

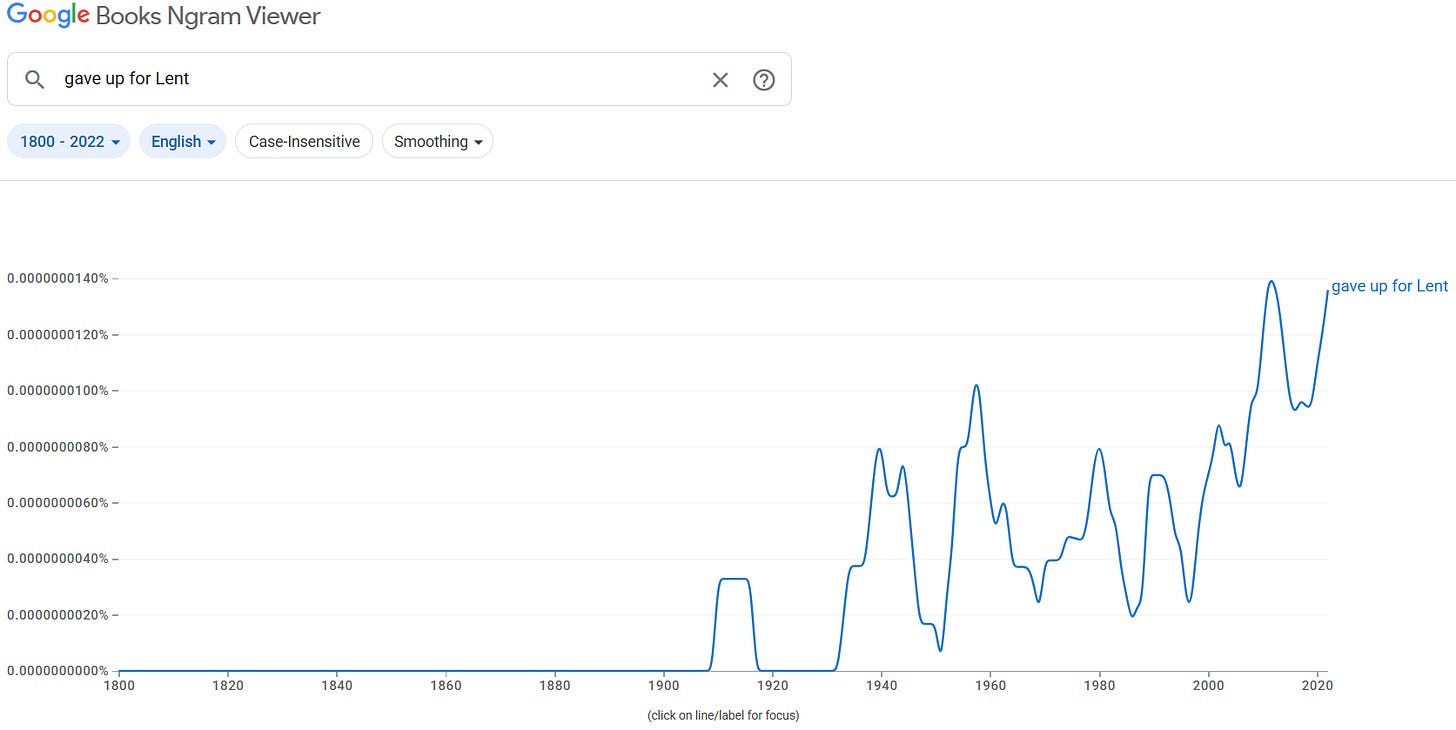

This is surprising for two reasons. First: as far as I can tell, the practice of “giving something up for Lent” in this individual way did not exist before 1900. Here’s a Google Ngram:

This practice appears to have arisen in direct response to the Church loosening its dietary laws. That’s the second reason it’s surprising! In the early twentieth century, the Church repealed a lot of official penitential disciplines, while encouraging Catholics to either voluntarily keep the practice or develop “alternate forms of penance.” We saw this already with meatless Fridays and the Eucharistic fast. This always failed. Catholics simply abandoned the discipline altogether.

Except here. For whatever reason, when Lenten fasting was rolled back, Catholics did, apparently, adopt alternate forms of penance en masse. I would love to read a paper on why this was received so differently.

The private forms of penance we practice are not perfect. Many Catholics, operating without real guidance from their pastors, try to give up sins or vicious habits for Lent, like “pornography” or “doomscrolling.” You aren’t supposed to give up bad habits for Lent. You are a Christian. You are supposed to give up bad habits all year round! The point of fasting is to give up good stuff. As Pope, I would gently clarify this.

Nevertheless, the private forms of penance are a good, healthy discipline. If the pope were to bring back six-days-a-week fasting and abstinence out of the blue, there is a real risk that he would fatally disrupt the modern private practice while failing to actually restore the ancient practice. When it comes to the disciplines, the pope must be humble about what he can practically accomplish. Yet the Orthodox show us that we really could be doing more, as a Church, to prepare our hearts for the Lord in Lent.

So, if I were pope, I would make a prudent, fairly modest change: restore fasting (in addition to meat abstinence) to all Lenten Fridays. If that went well, then, ten years later, I might add Wednesdays and/or dairy abstinence and/or abstinence from sex.7

When We Feast, We Feast!

A very wise priest8 once said, “Ah, Catholics! When we feast, WE FEAST! When we fast… we cheat!”

Why shouldn’t we? We are an Easter people! Christ has defeated the grave! His resurrection and the joy that comes with it is always sprouting up unexpectedly, even in seasons of penance.

For example, all fasting is suspended on holy days. What counts as a holy day, you ask? There are 16 solemnities on the calendar (not all of them include an obligation to attend Mass)… plus every Sunday on the calendar is a holy day, so throw in another 52. If you are giving things up on a Sunday in Lent, stop. Go feast. The GIRM demands it.9 That’s why Catholic Lent has 46 days in it: 40 days of fasting, like Christ in the desert, plus 6 Sundays of feasting. This dates back at least as far as Pope St. Gregory the Great.

(The Orthodox do it even harder. For all their rigorous fasting, they suspend it on both Saturdays and Sundays—following the Canons of the Council in Trullo aka the Apostolic Canons—which means they make Lent even longer to get a full 40-day fast in.)

Here’s another, less known “cheat”: on the Catholic calendar, days are measured midnight-to-midnight… except Sundays and solemnities. These holy days begin at the evening of the preceding day. Hence the Liturgy of the Hours for Sundays always has Evening Prayer I (for Saturday night) and Evening Prayer II (for Sunday night). This is also why vigil Masses in the evening on “Saturday” fulfill the Sunday obligation, but Masses on Saturday morning (for example, typical wedding Masses) do not. Liturgically speaking, it’s already Sunday! So quit fasting! There are few things better than pouring yourself a tall glass of chocolate milk with some Oreos after dinner on a Saturday night in Lent.

In recent years, I have learned that my view is controversial. Some learned commenters argue that there is a distinction between a Catholic liturgical day and a Catholic legal day. The liturgical day, they agree, runs sunset-to-following-midnight, but penances and fasting (they argue) are tied to the legal day and therefore run midnight-to-midnight.10 This strikes me as unnecessarily complicated and spiritually baseless. It seems absurd that I could celebrate the Feast of St. Joseph in the evening because it is liturgically his solemnity, but then be barred from actually feasting St. Joseph because it is legally not his solemnity for six more hours.

Fortunately, the premise of this series is that I’m the pope. Pope James is officially clarifying this one in favor of the “cheaters,” hands down.

One more change I would make in the spirit of feasting: under current law, Friday fasts are suspended during the octave of Christmas and the octave of Easter. To further emphasize the joy of the Church, Pope Celestine VI (me) would suspend Friday fasting for the entire season between Christmas and Epiphany and between Easter and Ascension Thursday. The Incarnation and the Resurrection are the most important events in human history, and our joy over them should not be interrupted. When we feast, we feast!

Ascension Thursday on Ascension Thursday

The Feast of the Ascension is a high holy day. All Catholics are obligated to attend Mass. It falls on the fortieth day after Easter. Traditionally, there’s a whole octave of celebration after it—eight days!

However, in many countries where Ascension is not a public holiday (including the U.S.), the feast is transferred to Sunday. I don’t mind if, say, Immaculate Conception occasionally gets transferred or abrogated, but, come on, Ascension is on a Thursday every year. It always gets transferred to Sunday.

That’s just silly. This is a major feast. The Risen Christ rose up into Heaven and we’ve been waiting for Him ever since. Go to Mass. Permission to fiddle with Ascension Thursday is revoked.

Plus, if Ascension Thursday is on Thursday and it’s celebrated as an octave, with no fasting in the octave… that’s not one, but two extra Meat Fridays! When we feast, we feast; when we fast…

Well, you know the rest.

NEXT VOYAGE:11 more disciplinary changes, focusing on the liturgy and priestly formation, including my pitch for married priests. (Hear me out!) In other work, I think I’m due for a Worthy Reads and I’m torn between writing about moral immigration principles, my pessimism about mass killings like the Annunciation massacre, and a (final?) follow-up on my lengthy obsession with net neutrality.

For the rest of this series, see:

An important note: in this article, I am generally talking about what the Pope ought to do in his role as patriarch of the Western Church, not in his role as pastor and teacher of all Christians. Although the pope has universal jurisdiction, it is usually inappropriate for him to exercise it on matters of mere discipline outside the Latin Church.

Therefore, the Eastern Catholic Churches in communion with Rome would, in general, continue their own internal practices unmolested by these changes. Besides, my impression is that they are already well ahead of the Latin Church on many of these points.

Water and medicine excepted; young and infirm excluded; and with a general “use common sense” proviso.

Ask me how I know!

On second thought, don’t!

…with the usual proviso allowing exceptions in cases of necessity, or as a fallback if someone forgets and accidentally eats meat on a Friday.

A good alternate form of penance, in my view, would be to pray one rosary, or a good work of similar effort. This takes about 15 minutes, which is very manageable.

Full disclosure: in my family, for at least a generation, the designated alternate form of penance has always been to pray just one decade of the Rosary. I admit this is kind of weaksauce (it takes less time or effort than brushing your teeth), but I have been reluctant to change family tradition when the Church as a whole has effectively abandoned Friday penances altogether, and we are mostly doing a pretty good job staying meat-free anyway.

13% eliminated meat from their Friday diets in response to the change (28%*41%; see page 9), and 13% were already avoiding meat on Friday (72%*18%; see page 10). Even more heartening, an additional 15% said they had reduced meat consumption on Fridays, which suggests progress with more room to grow in the future.

In addition, 25% of U.K. Catholics reported they were unaware of the changes (see page 10), which is another growth opportunity… except I suspect that a very tiny fraction of that bloc is religiously Catholic.

Of course, it bears mentioning that the British Church was much slower to adopt the “alternate forms of penance” concept than most other national churches in the first place—they made the change in 1985, not 1966 like most—so it shallower roots. I expect results in America would lag behind this.

One should be very careful about adding any penitential abstinence from sex. The days on which faithful Catholic couples can have sex is already, in many cases, very limited. Couples using Church-approved fertility awareness methods to space their children are already prevented from having sex for about half of every month. (More, if anyone involved has qualms about sex during the bloody days.) Catholics with irregular cycles or who are nursing may have far less opportunity. This is in addition to the usual practical barriers to having sex: they’re exhausted from taking care of their existing children, he has a headache, she has a cold. Some couples have military deployments to contend with, or debilitating illnesses, other large obstacles to regular conjugal life.

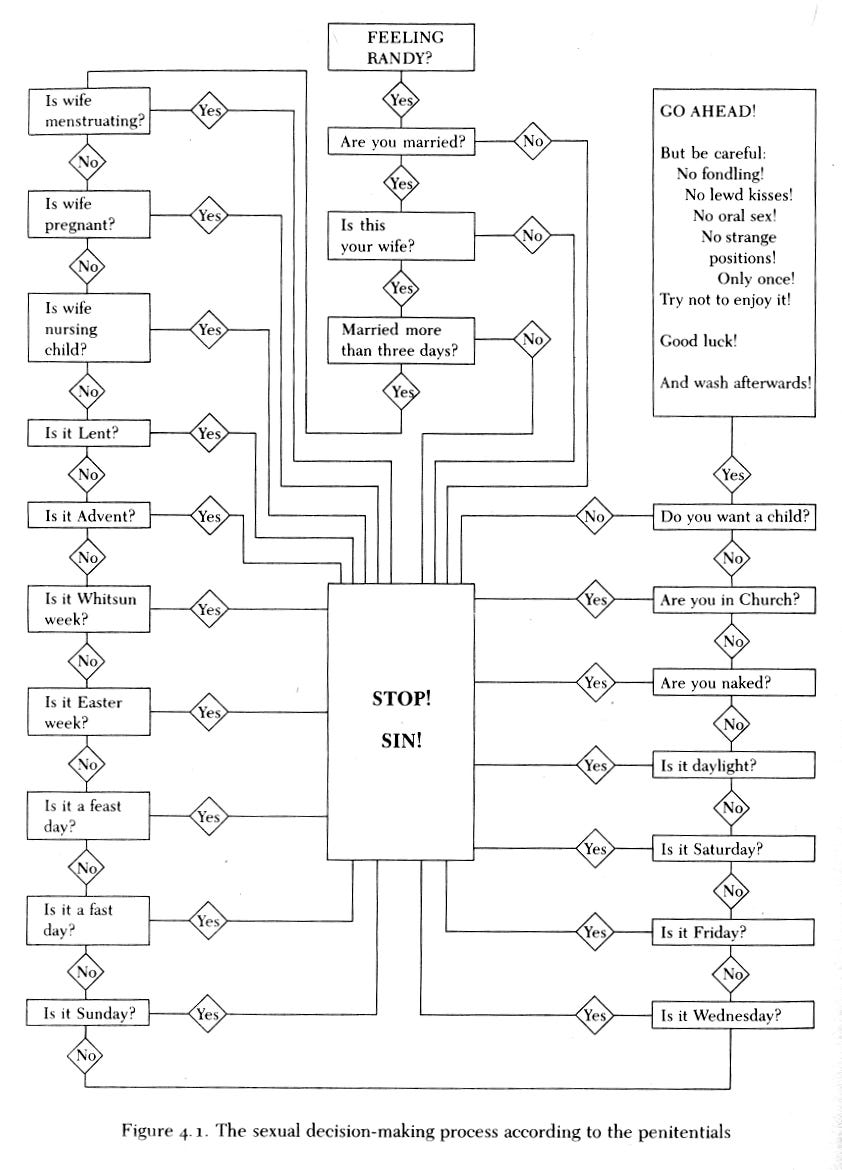

When you take all this and start adding extra days where the Church forbids sex just because of the liturgical season, the burden gets heavy much faster than you’d expect, as the sex-abstinence days consume some of the sometimes very limited opportunities good Catholic couples have for intimacy. There’s a notorious flowchart from Prof. James Brundage’s Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe that makes this point rather emphatically, even though it is significantly exaggerated:

This is exaggerated because it takes the most extreme position ever suggested by a penitential, with absolutely no nuance, and suggests that it is the actual teaching of the medieval Church, or the practical reality on the ground for medieval peasants. Neither is the case. For example, the Church has occasionally discouraged, but never forbidden, sex on a feast day. Far from instructing couples “not to enjoy it,” the Church long taught that couples have, to some extent, a moral obligation to earnestly pursue and obtain orgasm for both husband and wife. I present a more balanced view of the Church’s traditional sexual teachings in my translation of Bishop Kenrick’s De Usu Conjugii.

That said, I’m sure medieval penitential guides can be found which teach every single one of these things, so it’s not that Brundage was wrong, just that this flowchart, standing alone, lacks context. (Heck, for all I know, Brundage included all that context in the actual book, but the chart has become independently famous and is nearly always presented as a guide to the actual sex rules for medieval peasants.)

Anyway, I digress. My point was that one must be cautious about adding sex-abstinence days to the Church’s official fasting calendar.

However, at the same time, sex is the perfect thing to fast from. It is hugely good, and it is hugely distracting from the higher things of the Lord. Adding six sex-free days to the Church calendar would probably do quite a bit more good than harm… but adding forty or fifty almost certainly wouldn’t.

I could be mistaken, but I believe this was the great Fr. Michael Tavuzzi, O.P.

The USCCB has an FAQ on their website that kinda-sorta disagrees with me on this point:

Apart from the prescribed days of fast and abstinence on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, and the days of abstinence every Friday of Lent, Catholics have traditionally chosen additional penitential practices for the whole Time of Lent. These practices are disciplinary in nature and often more effective if they are continuous, i.e., kept on Sundays as well. That being said, such practices are not regulated by the Church, but by individual conscience.

This is mealy-mouthed, but, to the extent that it takes a position, it is incorrect. Sundays are feast days. Feast.

My own bishop, the subject of that article, has cleverly avoided making his own view perfectly clear. I know two canon lawyers who work for him. One of them, whom I very much like and respect and who has vastly more knowledge than I do on this, disagrees with my view on this, and sees no problem with a distinction between the liturgical day and the legal day.

My papal decree jossing his interpretation will therefore taunt him, by name, which I think is the only responsible papal choice in that situation, don’t you?

LLM Disclosure: In this article, and probably others in the series, I am running AI title tests. First, I come up with a title for the article. (In this case, I came up with “Fast Fasting Fixes,” because I am a sucker for alliteration.) Then, I feed the article into GPT and ask it to generate one title, optimized for social media. (This time, GPT gave me “Bring Back the Fast,” which I corrected to “Fasts.”)

When the article launches, a quarter of you get this article in your inbox with my title on it, a quarter of you get the LLM title, and the other half gets nothing. Whichever title generates the most inbox clicks in the first hour after launch automatically becomes the permanent title of the article, and it is then emailed to the remaining half of De Civ’s subscribers.

I earnestly hope to beat the clankers here, but the only way to know is to try.

You've heard of work hard, party hard ?

Get ready for fast hard, feast hard.

I'm pretty much with you on fasting, James. I observe a fast every Friday during Lent, as well as the 2 official fast days which by themselves, are extremely nominal).

Fr. Z supports a former practice, the Ember day fasts on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday, 4 times a year.