I Am Interviewed by Jonathan Frakes, Again

"Two-Takes Frakes" is back at De Civitate!

When acclaimed actor-director Jonathan Frakes (A Biltmore Christmas, Busted: Thunderbirds Are Go) reached out to me for another sit-down interview, I admit I was hesitant. After last year’s inexplicable tape malfunction, I thought it might be tempting fate to try again. Still, the co-star of A Klingon Challenge was persistent, and he wore me down. Finally, I agreed to clear some time on my calendar today, April 1st.

Then—wouldn’t you know it?—it happened again! Once again, I have a complete transcript of my interview with Jonathan, but my answers vanished from the videotape! The only part of the recording that survived is his questions for me. You’ll have to read on to see my answers!

We've all heard the expression, "Clothes make the man." But is it really true?

I used to think I knew the answer to this. Now, I don’t.

I found out this year that my wife wears clothes that make her feel cute, because they make her feel cute. This shocked me.

I wear clothes to make others respond to me appropriately. A suit to impress, a polo for work, a t-shirt for hanging out… and, really, does an adult man need any pants besides khakis?1 These clothing choices put others at ease, and, as long as I’m comfortable in them, I’m happy. (If I don’t want to put others at ease, I may wear something deliberately incongruous, like a suit to a work lunch.) Why would I care what I’m wearing? I’m not looking at myself, and I hardly need to put myself at ease with me!

Clothing, on this view, is irrelevant to my inner self. Clothing has no direct effect on me beyond its basic functions. “The clothes make the man” was made up by tailors to sell expensive shirts.

It seems strange to write this out, since I always assumed that basically everyone felt this way about clothes, so I suspect I’m just telling you what you already know.

I’m not so sure anymore, though. I’ve asked around a bit, and it seems quite a few people out there wear clothing because it makes them feel a particular way. “Cute” or “romantic” or “hangry” or whatever. For those people, perhaps clothing does make the man?

However, I’d like to reassure you that those people are all weirdos.

Did you have a favorite book as a child?

Oh, yes. It was called Pompeii… Buried Alive!

When I was three-going-on-four, I asked my parents to read this to me over and over again. I loved seeing the ancient Roman world. I thought the volcano itself was amazing. The thrill of imagining myself trying to escape the eruption, or sitting across the bay in Naples with Pliny, watching, was wonderful.

And then the second half of the book: scientists exploring Pompeii! The plaster casts! The seismologists! What amazing people! (I desperately wanted to be an astronaut-scientist when I grew up.2) Then it ends on a deliciously ominous note:

It is a peaceful day in Pompeii. The giant is sleeping. When will the giant wake up again?

Nobody knows.

Seriously, this book had it all. There were some great call-and-response bits that made it extra-fun to read aloud.3

One night, after it had been read to me something like thirty-three thousand times, I was leafing through the book in my bed, looking at the pictures. I wished someone could read me the actual story again, because pictures weren’t enough. Then it occurred to me: I can give it a shot. Why not? I could try to read the first word. The worst thing that could happen is that I can’t read it, and then I’m no worse off than I am now. It was a long shot, but I might get some frisson of the pleasure of having Pompeii! read to me, so I took it.

I tried the first word and was astonished to find that I understood how the letters fit together. Then I tried the second word. Reader, I read the whole book! The sense of astonished satisfaction I felt as I started the last chapter is one of the lasting memories of my childhood.

(Naturally, my parents figured I had simply memorized the book and that I mistakenly believed recitation was reading, but we soon put that theory to rest.)

One more memory linked to this book: in Kindergarten, every kid got one day to bring in a parent to read a favorite book to the class. By then, I was mostly into The Hardy Boys, but you can’t read The Missing Chums to a classroom, so I picked my still-favorite picture book, Pompeii… Buried Alive!.

You can imagine how that went: me sitting up at the front while everyone in Pompeii is brutally killed, beaming up at my mother, who is looking out at the class in a sort of mild panic as it dawns on her that this is not the kind of book they usually read. One girl seems on the verge of tears. Mom soldiers on. I continue beaming, and clap at the end.

Man, looking back, Mrs. Bernabi had to put up with a lotta weird stuff from five-year-old me!

Do you have a favorite method of falling asleep?

I lie down. I close my eyes. I’m asleep in maybe two minutes. There’s no trick to it.

It helps, probably, that I only sleep about six and a half hours a night. By the time I crawl into bed, I’m usually pretty darned tired.

Is there anything more precious than the gift of sight?

deez nuts!

Who can explain the mystery of music?

Music seems really weird.

All my thoughts about this are probably really stupid. I’m sure Aristotle did a much better job covering music in his work on aesthetic philosophy thousands of years ago, and surely many have followed in his footsteps.

Nevertheless, here are six interesting features of music that would keep me up at night if I didn’t fall asleep so easily:

Songs seem to be examples of those immaterial patterns I’m always banging on about—the ones that combine with matter to make up the visible universe. Their material component is unusual compared to so-called “ordinary objects.” Unlike a chair, which is basically a bunch of atomic LEGO bricks stuck together, a song being sung is a vibration moving through the atmosphere, passed from atom to atom until it strikes your ear. We tend to identify the song more with the immaterial pattern than with the material vibration.

Yet songs seem to have matter-independent existence: I’m fairly sure the song “Do One Thing At A Time,” which I wrote which I was maybe eight, and which has only ever played in my head, is nevertheless a real song.4 Certainly I hear it in my mind often enough!

Music moves us in profound ways, along a variety of dimensions. Thanks to the romantics, people today talk about music in terms of how it enkindles emotions, but music moves us in many other ways, too. One drab but uncontroversial example: it’s very common for people to rely on a playlist to help them focus on a task. Far fewer people feel this way about a chair. More controversial: the right piece of music, at the right moment, can offer the listener a glimpse of something… beyond itself. From this comes great inspirations, creative and otherwise. (You either recognize this experience or you don’t.) I have never felt that way about a chair, even a very nice chair.

The thing that moves us about music appears to be precisely its patternedness. No particular melody or rhythm seems to be privileged. Kids grow up to love whatever harmonies they were raised with, even though people raised within other musical traditions will find it painful and dissonant. Meanwhile, the people who get really really into music tend to slowly fall away from anything recognizable to normies as melody or rhythm. They delve deeper and deeper into more and more abstract patterns. (Then they arrive—apparently inevitably—at Bach.)

According to the Bible, angels sing a lot. Singing appears to be the primary angelic activity in Heaven.5 This is very strange, since song, at least as we experience it, requires both matter and form. But angels have no matter, only form.6 They have no lips with which to force vibrations into the air. They have no ears by which to hear them. I’ve already digressed a lot, so I won’t go down this rabbit hole, but there probably isn’t any air in Heaven for sounds to propagate through. So what are angels doing, exactly? Praising God through patternedness, I suppose, and the closest human analogue the inspired writers of Scripture could come up with was song.

This suggests, in turn, that singing (even more so than reasoning) is, maybe, the closest thing humans have to angelic activity. Animals, notably, don’t sing songs. They make melodic noises and occasionally use those sounds to communicate useful data, but, at least to my knowledge, there is no animal equivalent of “O Domine Jesu Christe” by Tomas Luis de Victoria, or “Broken in All the Right Places” by i am jen.

Again, I’m sure none of my insights are original, and some of them might be laughably wrong. But aesthetic philosophy is, sadly, a gap in my self-education, so all I have are these informal thoughts about the “mystery of music.” I’m sorry I can’t be of more help to you, Frakes.

Do we make our own luck?

In a sense, yes.

The world (at least above the quantum scale) is mostly deterministic. Most of what we perceive as “random” isn’t actually random. A sufficiently well-informed physicist, with sufficiently detailed information about the initial state of a bingo cage (or similar apparatus) and the forces that are going to be applied to it, could, given sufficient time to perform the calculations, tell you exactly what the winning lottery numbers are going to be. However, nobody has the time to perform those (incredibly sensitive) calculations, and lottery officials deliberately make it extremely difficult to get this information (which would require extremely sensitive measurements). Winning the lottery, then, comes down to luck instead.

So we see that luck—and, more broadly, probability—are, essentially, ways of describing the things we don’t know, with some guidance from the things we do know. (I am aware that Slate Star Codex disagrees, but I think I probably should not turn this answer into a three-thousand word argument about frequentism.)

[FRAKES: “Yes, absolutely, I do indeed concur wholeheartedly. Let’s move on, please?”]

Building on that: if the world were perfectly deterministic, everything could, in theory, be calculated, and luck could, therefore, be abolished. Indeed, this is basically how Trin Tragulua built the Total Perspective Vortex.

[FRAKES: “Shut up!”]

I beg your pardon?

[FRAKES: “As in close your mouth and stop talking! I said let’s move on.”]

Um… okay?

I do not think the world is perfectly deterministic [FRAKES: *reacts*], mainly because we are in it. My (admittedly fairly new) belief in libertarian free will commits me to believing that there is at least some element of human behavior that cannot be predicted—or even mapped to a probability distribution.

Still, the region of events we call “lucky” or “unlucky” can be shrunk dramatically just by collecting more data, analyzing it better, and thinking more carefully about the implications. You’ll never eliminate luck, but you can make it a lot less important.

So, uh, think good, I guess!

Next question.

Can a home ever be truly safe?

No corruptible thing is ever truly safe.

I am the sort of person who, when told by an insurance agent that I really didn’t need to buy optional flood insurance, checked an elevation map to confirm that my house is more than 400 feet above the river’s water level, and that all of Minneapolis would be underwater before the floodwaters lapped at the edges of my neighborhood, before I finally agreed.

“Checking elevation maps,” by the way, is one way of making your own luck, by decreasing the available probability space for—

Okay, okay, I’m sorry!

Have you checked the back sections of newspapers and magazines lately?

Do they still have back sections? That’s what they used to call the classifieds, right?

I have not physically seen a newspaper in months. The magazines I get are What’s Happening In West Saint Paul and Highlights for Children. I can honestly say that I have not checked their back sections (because I don’t think they have them).

What is the secret of the green thumb?

Please write me if you find out. I’ve always figured it was exactly following the plant’s directions for care, and that my plant failures must be due to insufficiently rigorous direction-following. Makes sense to me.

However, it took me an alarmingly long time to deduce the correct parameters for cooking a hamburger given the imprecise and incomplete directions people are prone to giving, so maybe don’t listen to me.7

What mysteries lie within the frame of a portrait?

I dunno, man, feels like we just talked about aesthetic philosophy a few answers ago. Life, the universe, everything.

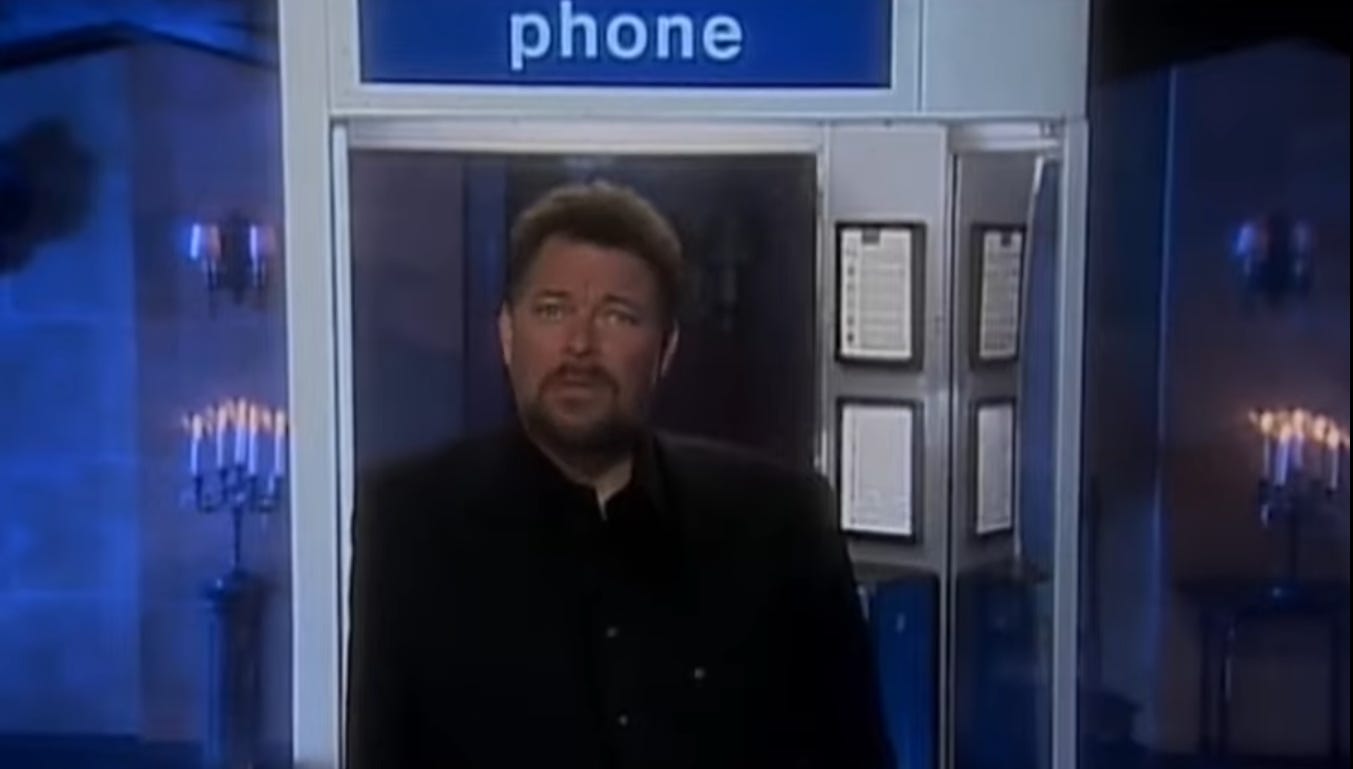

How many dramas have taken place in these tight little boxes?

Eight hundred and eighty-four, plus that one Sarah Jane Adventures episode where it materializes, plus “The Telephone Rock”:

So eight hundred and eighty-six dramas have taken place in one of these tight little boxes.

How do you describe terror?

I have been told that English, because it is influenced by so many other languages, has a relatively huge number of redundant synonyms.

The boring way to approach that is to just treat all the redundant synonyms as synonyms. On this approach, we might say that terror is fear, an emotion felt in reaction to perceived threat.8 ‘Terror’ would be perfectly interchangeable with ‘anxiety,’ ‘alarm,’ ‘fright,’ or ‘dread.’

Boring!

The other approach is to figure out what each word wants to mean. Let their shades of meaning bloom!

In The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt draws an interesting distinction between “fear” and “anxiety”: anxiety is a reaction to future perceived threat, while fear is reaction to present perceived threat. I’m going to buy that because it feels right, and this is a live interview, so you can’t fact-check me. Terror, it seems to me, is also a reaction to present threat, so much more akin to fear than anxiety.

Etymologically, “terror” comes to us from Latin (via French). The original Latin (terror) just meant “extreme fear (panic, alarm),” but Michael de Vaan links it to words meaning “tremble,” “shiver,” and even the name of a goddess (invoked as a curse). It is from this root that we get the word “terrible” and the phrase “night terrors.”

Meanwhile, “fear” originates from Germanic/Dutch words (vâre, fâra) meaning “danger,” “ambush,” and “strategem.”9 This is interesting. It suggests that fear is something that you can fight. It may even spur you on. It evokes the fearful atmosphere of a horror movie like Saw or Alien, where the protagonist’s fear drives her to keep her wits about her, stay alert, form a “strategem,” and survive.

“Night terrors,” by contrast, are a blind, screaming panic. There’s no strategy anymore; the mind is fully subsumed by the reaction to threat. It freezes rational thought, rather than protecting it, rather like beholding that angry curse-goddess. Something “terrible” induces such fear that it comes back around to “awe,” which suggests helplessness and trembling in the face of an overwhelming threat, rather than industrious attempts to escape the threat.

That, then, is how I would describe terror: an emotional reaction to a current perceived threat that overwhelms rationality, causing an irrational response, such as freezing up, trembling, running like the kid in The Red Badge of Courage, and/or (in certain rare individuals) recklessly attacking.

Have you ever noticed the curious things one sees discarded by the roadside?

Are you talking about those (very tempting) couches and chairs left by the curb with a “free” sign on them, or, like those fenders lying in the gutter on the highway that were clearly wrenched violently off in some horrible accident and then not cleaned up?

Who knows why certain people say certain things?

That doesn’t answer my qu—

…or does it?

Have you ever experienced a sleepwalking episode?

No. I lucid dreamed once, when I was a child, and that was really cool.

Is there a more important job than that of a teacher?

Preface: my parents are teachers. My grandfather was a teacher. My mother-in-law is a teacher. A bunch of my cousins are teachers. All my favorite childhood teachers were teachers.

Teachers are an important profession. I like teachers. They’re doing valuable work. However, they do not have “the most important job.” Even if they did, it would not make them nearly important enough to justify the secular canonization our culture has given them.

Yes, here it is, my hottest take of the day: teachers are mid.

Of course, “most important” is said in many ways. Let us survey some of them:

Most important for physical well-being of the species: farmers

Most important for spiritual well-being of the civilization: priests

Most important for physical continuation of the species: parents

Most important for spiritual continuation of the civilization: also parents

Most important for utility accomplished per minute: doctors?

Most important for utility at great personal risk: loggers? trash collectors? construction workers? (tbh I thought cops would place higher on this list.)

Most important for having the highest and greatest goal: theologians

Most important for being most conceptually fundamental: philosophers

I am not committed to any of these answers, but I am reasonably confident that teachers don’t come in on top of any category. (“Parent” finishes surprisingly well in most of them, though.)

Where teachers seem to stake their claim to importance is in the “spiritual continuation of the civilization” category. Teachers are hired by parents (sometimes indirectly, through the parents’ government) to pass on knowledge, wisdom, and moral values to their children, in loco parentis. The intensity of this relationship (modern teachers often see their kids for several hours a day) makes teachers very important parental stand-ins.

Yet, with a rotating cast of teachers that changes annually, in classrooms of 20-30 students, without the deep and permanent commitment a parent is expected to make, even a great teacher cannot replace even a bad parent, even under ideal circumstances.10

We should respect teachers as we respect fire fighters, policemen, chefs, nurses, pilots, and other skilled professionals. Teachers, I hasten to repeat, are doing valuable work as part of an important profession. But we gotta knock it off with the pseudo-worship.

That’s my take, Frakes. Cut it, print it.

Is there a more annoying sound then the screech of chalk against chalkboard?

Sandpaper.

It’s so coarse, and rough, and irritating, and it makes pained shivers shoot down all the diodes in my left side whenever I’m unlucky enough to hear it. I can’t really use sandpaper, at this point. Maybe I could if I wore those thick headphones autists use.

Also, what’s so bad about chalk on chalkboard? The bad one is nails across chalkboard, but even that’s not as bad as sandpaper. Chalk is built for chalkboards, and you’ve really gotta work it pretty badly to get even one good shiver of revulsion out of it.

Thanks for an enlightening interview, James. Happy April Fool’s Day!

Happy April Fool’s, Jonathan. Thanks for sitting down with me again.

Okay, yes, one set of dress pants.

I watched a lot of Star Trek. I loved, inter alia, Jonathan Frakes. I once fell in love with a business card because it used The Next Generation’s Crillee font, but I lacked the words to explain to my parents what was so amazing about the font, so I stood at the rails of the crib and gesticulated with frustration. (This is my earliest memory.)

Trivia specifically for my mother: Pompeii… Buried Alive! was the first book by Edith Kunhardt, the daughter of Dorothy Kunhardt, the author of Pat the Bunny, reportedly my favorite book when I was a baby. The Kunhardts really had my number!

To be clear, this is not a good song. It’s a song I wrote when I was eight. The lyrics for “Do One Thing At A Time” are, in toto:

Do one thing at a time!

Give every one attention,

Or you’ll never get a dime

for doing without tension!

This doggerel has been stuck in my head for nearly thirty years. Please send help.

(I will not share the tune here, since letting the tune out of my head would ruin the hypothetical. For the purposes of this exercise, pretend its tune is similar in tone and tenor to the average Clamavi de Profundis track. It isn’t, but whatever you imagine will be much less grating than what eight-year-old James apparently found charming.)

P.S. Being sincere, I’ve probably hummed “Do One Thing At A Time” to myself a few times out loud, so the song probably has been materially instantiated. But it’s easy enough to imagine a song that’s never been sung, only played in your head, so stop fighting the hypo.

Some hold that, when biblical angels are said to “speak” in verse, this does not necessarily imply that they are singing. I don’t agree, since some verses are explicit that they’re singing.

My eldest daughter received this book at her baby shower:

Whoever gave this to us, kudos, it was a big hit with my daughter. However, the book was really big on angels being in specific locations and doing particular physical activities, so I had to clarify on every page: “…but not literally, because angels have no matter, only form.”

My wife once caught me reading this page as, “Angels are close by at the end of the day… but not literally, because angels have no matter, only form,” to the chubby, gormless six-month-old baby bouncing on my lap, and thought it was about the funniest thing she’d ever heard.

But my kids know that angels have no matter, only form, so it worked!

…Okay, fine. I see the look you’re giving me. I see the question in that look.

Ten years. It took me ten years from my first serious attempts at cooking a burger to my first burger that was enjoyable to eat.

I experimentally varied patty diameter, patty thickness, cooking temperature, and cooking time, trying to identify what I was doing wrong—but, like a good data-collector, I only varied one of these at a time. Unfortunately, all four parameters were wrong, and typical online recipes do not specify any of them beyond vague pabula like “cook over medium heat.”

Now, my stove top dial runs from 1 to 8. As I eventually learned, “medium” heat does not mean a 4. It means 1.5 to 2. Either my stove runs hot or stove makers need to update their definitions. Others seem to intuit this sort of thing. Perhaps they use that same intuition to keep their plants alive—in defiance of vague or incomplete directions.

I make pretty good hamburgers now.

Suddenly, Diogenes leaps out of a bush! Diogenes is holding a man purple with outrage (because he’s just been kidnapped by Diogenes).

The man is swearing angrily, repeatedly demands a duel, and is trying to call his lawyer on his cell. He is reacting to a perceived threat with outrage. Diogenes says, “Behold! A terrified man!” and disappears.

I shrug. It’s hard to be very specific when describing any emotion. Your good friends Levar and Brent explained this in a scene you weren’t in, Jonathan:

LAFORGE: No offence, Data, but how would you know a flash of anger from some odd kind of power surge?

DATA: You are correct in that I have no frame of reference to confirm my hypothesis. In fact, I am unable to provide a verbal description of the experience. Perhaps you could describe how it feels to be angry. I could then use that as a reference.

LAFORGE: Well, okay. When I feel angry, first I feel hostile.

DATA: Could you describe feeling hostile?

LAFORGE: It's like feeling belligerent, combative.

DATA: Could you describe feeling angry without referring to other feelings?

LAFORGE: No, I guess I can't. I just feel angry.

DATA: That was my experience as well. I simply felt angry.

You know the interior difference between a fear reaction to perceived threat and an anger reaction to perceived threat, but it’s not very easy to describe that difference in non-tautological terms.

This from the Oxford English Dictionary, the One True English Dictionary.

Huh, I winced just watching the end of the Frakes video, but I find the sound of sandpaper if anything pleasant. Took a very brief detour to try to find why people find these sounds unpleasant (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chalkboard_scraping), but the hypotheses all seem pretty unconvincing (sounds similar to primate mating calls???).

Re Clothing:

Clothing, and in a broader sense, fashion in general, is the first communication that you have when you meet someone in person. Why should this communication not also work as a form of communication with yourself?